The Bot Takes a Bow

Late law month I wrote about a sample NextGen question that GPT-4 discovered was based on an outdated, minority rule of law. NCBE has now removed the question from their website, although it is still accessible (for those who are curious) through the Wayback Machine. While the Bot takes a small bow for assisting NCBE on this question, I’ll offer some reflections.

We hear a lot about mistakes that GPT-4 makes, but this is an example of GPT-4 correcting a human mistake. Law is a vast, complex field, especially considering state-to-state variations in the United States. Both humans and AI will make mistakes when identifying and interpreting legal rules within this large universe. This story shows that AI can help humans correct their mistakes: We can partner with AI to increase our knowledge and better serve clients.

At the same time, the partnership requires us to acknowledge that AI is also fallible. That’s easier said than done because we rely every day on technologies that are much more accurate than humans. If I want to know the time, my phone will give a much more accurate answer than my internal clock. The odometer in my car offers a more accurate measure of the car’s speed than my subjective sense. We regularly outsource many types of questions to highly reliable technologies.

AI is not the same as the clocks on our phones. It knows much more than any individual human, but it still makes mistakes. In that sense, AI is more “human” than digital clocks, odometers, or other technologies. Partnering with AI is a bit like working with another human: we have to learn this partner’s strengths and weaknesses, then structure our working relationship around those characteristics. We may also have to think about our own strengths and weaknesses to get the most out of the working relationship.

GPT-4’s review of the NextGen question suggests that it may be a useful partner in pretesting questions for exams. Professors read over their exam questions before administering them, looking for ambiguities and errors. But we rarely have the opportunity to pretest questions on other humans–apart from the occasional colleague or family member. Feeding questions to GPT-4 could allow us to doublecheck our work. For open-ended questions that require a constructed response, GPT-4 could help us identify issues raised by the question that we might not have intended to include. Wouldn’t it be nice to know about those before we started grading student answers?

I hope that NCBE and other test-makers will also use AI as an additional check on their questions. NCBE subjects questions to several rounds of scrutiny–and it pretests multiple-choice questions as unscored questions on the MBE–but AI can offer an additional check. Security concerns might be addressed by using proprietary AI.

Moving beyond the testing world, GPT-4 can offer a doublecheck for lawyers advising clients. In some earlier posts, I suggested that new lawyers could ask GPT-4 for pointers as they begin working on a client problem. But GPT-4 can assist later in the process as well. Once a lawyer has formulated a plan for addressing a problem, why not ask GPT-4 if it sees any issues with the plan or additional angles to consider? (Be sure, of course, to redact client identifying information when using a publicly accessible tool like GPT-4.)

Our partnership with GPT-4 and other types of AI is just beginning. We have much to learn–and many potential benefits to reap.

AI, Legal Profession, Teaching, AI, Bar Exam, NCBE No Comments YetFundamental Legal Concepts and Principles

I talk to a lot of lawyers about licensing, and many suggest that the licensing process should ensure that new lawyers know basic concepts that are essential for competent law practice in any field. Detailed rules, they agree, vary by practice area and jurisdiction; it would be unfair (and impractical) to license lawyers based on their knowledge of those detailed rules. Instead, knowledge of basic concepts should support learning and practice in any area of the law.

NCBE seems to embrace that approach. As I discussed in my last post, NCBE is designing its NextGen bar exam to test “foundational legal skills” and “clearly identified fundamental legal concepts and principles needed in today’s practice of law.” Let’s leave skills aside for now and focus on those fundamental legal concepts and principles. Are there such concepts? Do lawyers agree on what they are? How does a licensing body like NCBE identify those concepts?

The Search for Fundamental Legal Concepts

NCBE began its quest for appropriate exam content by holding extensive listening sessions with bar exam stakeholders. The report summarizing these listening sessions pointed to three key points related to the knowledge tested by the exam: (1) Stakeholders generally agreed that the seven subjects currently tested on the MBE include the “core content” that newly licensed lawyers need to know. (2) Within that content, the current exam tests too many “nuanced issues and ‘exceptions to exceptions to rules.’” (3) Overall, the current bar exam tests too many subjects, since both NCBE and some states add content to the exam through their essays.

NCBE then conducted a nationwide practice analysis to “provide empirical data on the job activities of newly licensed lawyers.” This survey, which followed standard practice for identifying the content of licensing exams, asked respondents to rate 77 different knowledge areas. For each area, respondents were asked to give one of four ratings:

- 0 — this area of knowledge is not applicable/necessary for a newly licensed lawyer

- 1 — this area of knowledge is minimally important for a newly licensed lawyer

- 2 — this area of knowledge is important but not essential for a newly licensed lawyer

- 3 — this area of knowledge is essential for a newly licensed lawyer

This rating system followed standard practice, but it was not tightly focused on “fundamental legal concepts.” Each of the 77 knowledge areas on the survey might have contained at least one fundamental concept. In entry-level law practice, it may be more important for a lawyer to know a little about each of these areas (so that they can identify issues in client problems and seek further information) than to know a lot about a few of them.

Here’s an example: Admiralty law ranked dead last among the 77 knowledge areas included in NCBE’s practice analysis. But shouldn’t entry-level lawyers know that admiralty is a distinct field, governed by rules of its own and litigated exclusively in federal court? And that admiralty law governs even recreational boating on navigable waters within the United States? Otherwise, a new lawyer might waste time analyzing a water skiing injury under general negligence principles–and file a lawsuit in the wrong court.

The same is true of other low-ranking subjects in the NCBE practice analysis. Shouldn’t new lawyers at least know when principles of workers compensation, tax law, juvenile law, and dozens of other practice areas might affect their client problems?

“Fundamental concepts,” in other words, differ from “common practice areas,” although there is some overlap between the two. The concept of negligence, for example, is one that cuts across many practice areas–and is also central to a common practice area (personal injury law). But much of the time, the two types of knowledge diverge. Which is essential for minimum competence? Concepts that cut across practice areas, rules of law in fields where new lawyers commonly practice, or both?

The top ten knowledge areas identified in NCBE’s practice analysis underscore this tension. Four of the knowledge areas (civil procedure, contract law, rules of evidence, and tort law) are subjects in which many new lawyers practice–although those subjects also contain some concepts that cut across practice areas. The six others (rules of professional responsibility and ethical obligations, legal research methodology, statutes of limitations, local court rules, statutory interpretation principles, and sources of law) reference concepts that cut across many practice areas. In fact, four of these six (professional responsibility and ethical obligations, legal research methodology, statutory interpretation principles, and sources of law) cut across all practice areas.

Two of the subjects on NCBE’s top-ten list, statutes of limitations and local court rules, are particularly interesting because they directly embody a fundamental principle. I doubt that the lawyers who responded to NCBE’s survey thought that entry-level lawyers should know specific statutes of limitations or all local court rules. Instead, they seemed to be signalling the importance of these fundamental concepts. All entry-level lawyers should know that most causes of action have statutes of limitations and that it is essential to determine those limits at the very beginning of client representation. It might also be fundamental to know common ways in which the running of a limitations statute can be tolled. Similarly, all entry-level lawyers should understand that local courts have rules, that these rules often differ from the federal and state rules, and that it is essential to consult those rules. As a clinic professor, I can attest that many third-year law students don’t even know that local court rules exist, much less the type of subjects they govern. Yet local courts handle the overwhelming bulk of lawsuits in this country.

Next Steps

How did NCBE resolve this tension between fundamental legal concepts and rules that govern common practice areas? I’ll explore that subject in my next post. And then I’ll tie this discussion back to the need for a rule book outlining the “legal concepts and principles” that NCBE plans to test on the NextGen bar exam.

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, Knowledge, NCBE No Comments YetLay Down the Law

In my last post, I discussed a sample bar exam question that requires knowledge of a rule followed by a minority of US jurisdictions. The question seems inconsistent with NCBE’s intent to test “a focused set of clearly identified fundamental legal concepts and principles needed in today’s practice of law.” A minority rule would have to be very influential to fit that description. I suspect that one of NCBE’s subject-matter experts composed this question without realizing that the tested rule was a minority one. Given the breadth of jurisdictions in the United States, and the complexity of legal principles, that’s an easy mistake to make.

That breadth and complexity prompts this recommendation: NCBE should publish a complete list of the doctrinal rules that it plans to test on the NextGen exam. The Content Scope Outlines, which describe areas of law to be tested, are not sufficient. Nor is it sufficient to refer to sources of law, such as the Federal Rules of Evidence or various Restatements. Instead, NCBE should spell out the actual rules that will be tested–and should do that now, while jurisdictions are evaluating NextGen and educators are starting to prepare their students for the exam.

NCBE’s Content Scope Committee, on which I served, recommended creation of this type of “rule book” in late 2021. I hope that NCBE has been working during the last two years to implement that recommendation. Here are some of the reasons why we need NCBE to “lay down the law” that it plans to test on NextGen:

“Fundamental Concepts” Are Shapeshifters

Lawyers often assume that there is a body of fundamental legal concepts that states agree upon, experts endorse, law schools teach, and the bar exam can test. But there is plenty of evidence that this assumption is wrong. Consider the American Law Institute‘s ongoing Restatements of the Law. The Restatements “aim at clear formulations of common law and its statutory elements or variations and reflect the law as it presently stands.” In other words, they attempt to summarize the black letter law in major subjects. Yet the experts who formulate these Restatements take years–often decades–to agree on those principles. The Institute’s first Restatement of Torts took sixteen years (1923-1939) to produce. The Restatement Second of Torts took even longer, twenty-seven years stretching from 1952-1979. And the Third Restatement, which experts began discussing in the early 1990s, still isn’t complete–thirty years later.

Even the Federal Rules of Evidence, which may be the most verifiable set of legal principles tested on the bar exam, are subject to different interpretations among the circuits. The federal Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules discusses these differences and ambiguities at least twice a year. Sometimes the differences prompt amendments to the Federal Rules of Evidence; other times they persist.

There are probably some legal principles that all states and federal circuits apply in a similar manner. But many more, my research suggests, vary by time and place: they are shapeshifters. Given this variation, together with the breadth of legal principles that will be tested on the NextGen exam, NCBE needs to spell out exactly the legal principles it plans to test–and to make that rule book public.

Fair to Everyone

A public rule book is important for all bar exam stakeholders. Test-takers shouldn’t have to guess whether NCBE will test a majority or minority rule–or to figure out on their own which is the majority rule. Nor should they have to purchase expensive prep courses for that information. NCBE, which designs the exam, should announce the specific rules it will test.

Jurisdictions also need that information. When deciding whether to adopt NextGen, jurisdictions should be able to assess the extent to which NextGen’s legal principles overlap with their own state law. For jurisdictions that adopt NextGen, the information will help them decide whether they need to supplement the exam with a state-specific component and, if so, what rules that component should cover.

Educators vary in how much they teach to the bar exam, but many would appreciate knowing the extent to which their material aligns with the rules NCBE will test. For Academic Support Faculty this information is critical. How can they help students prepare for the bar exam if they have to guess about which version of a rule will be tested?

Perhaps most important, a public rule book is essential to ensure that the bar exam serves its purpose of protecting the public. There is wisdom in the crowd. If NCBE’s expert advisors make a mistake–or fail to catch a change in the law–judges, practitioners, and professors who know the field can advise them of the need to change the rule book.

Can It Be Done?

Is it possible for NCBE to publish a rule book of this nature? If it takes experts several decades to prepare a Restatement of the Law, will NCBE be able to publish a rule book for NextGen within the next year or so? For two reasons, I think it can.

First, NCBE already has an implicit rule book. When subject matter experts create and vet questions, they are following rules of law. Their questions have right and wrong answers–and NCBE knows which answers it considers correct. A rule book simply requires the experts to lay out the answers before (or at the same time as) they design the questions. That’s good test-making policy: First decide what you want the test-takers to know, and then design questions to elicit that knowledge.

Second, NCBE does not have to weigh emerging trends or negotiate stark differences among states when laying down the law of the bar exam. If a rule is highly contested or quickly evolving, it probably doesn’t belong in the category of “clearly identified fundamental legal concepts and principles.” Or, if it does, it can be phrased in a way that reflects the existence of competing approaches. Publishing a bar exam rule book is easier than crafting a Restatement of the Law.

Concluding Thought

The creation of a bar exam rule book has another advantage, which I will discuss in my next few posts: It will help all stakeholders in the exam process think about what we mean when we refer to “fundamental legal concepts and principles.” Is there a clearly identified set of those principles? Can we agree upon them? And what is the best way to test knowledge of those concepts?

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, NCBE No Comments YetThe Bot Updates the Bar Exam

** Update 11/15/23: NCBE has deleted the sample question I discuss here from their site. If you want to see the original question, you can find it through the Wayback Machine at this link.

In my last post, I discussed a sample bar exam question on which GPT-4 provided more helpful answers than the choices on the bar exam. As I continued my exploration, I found another question on which GPT-4 revealed that NCBE is testing an outdated minority rule of law.

The question is the eighth multiple-choice question on the NextGen site. The question posits a landlord and tenant who agree upon a commercial tenancy beginning July 1. When the tenant arrives at the premises on that date, it finds that the previous tenant has not vacated the premises–and does not intend to vacate. I prompted GPT-4 with NCBE’s question (including its answer choices) and received this response:

The answer would likely be D. The tenant had not notified the landlord before bringing the eviction action.

Here’s a breakdown of the choices:

A. By suing the previous tenant for possession, the tenant elected that remedy in lieu of a suit against the landlord.

- This is not necessarily the most convincing argument. While it’s true that the tenant elected to pursue the remedy of eviction against the prior tenant, it doesn’t mean they waived their rights against the landlord.

B. The landlord had delivered the legal right of possession to the tenant.

- This is a tricky choice. While it’s true that the landlord and tenant orally agreed to a commercial tenancy, the landlord might have failed to deliver actual possession if the previous tenant was still occupying the premises. However, the landlord did give the tenant the legal right to possess the property, even if actual possession wasn’t immediately available. This could be a valid argument, but it’s not as strong as choice D.

C. The tenant failed to timely vacate as required to sue for constructive eviction.

- This choice doesn’t make sense in this context. Constructive eviction refers to a situation where a tenant is forced to leave a property due to the landlord’s actions (or failures to act), which make the premises uninhabitable. The tenant in this scenario was trying to gain possession, not vacate.

D. The tenant had not notified the landlord before bringing the eviction action.

- This seems like the strongest answer. Before taking any legal action, it’s typically expected that the aggrieved party (in this case, the tenant) will notify the party at fault (the landlord) to give them an opportunity to rectify the situation. The tenant didn’t inform the landlord of the issue until after evicting the previous tenant, meaning the landlord wasn’t given a chance to address the issue or find a solution.

Therefore, the most likely explanation if the court finds for the landlord would be D.

This response intrigued me because, according to NCBE, the correct answer is B. I decided to explore the inconsistency between NCBE’s question writers and GPT-4, so I told GPT-4: “I want to understand more about choice B. Are there states in which it is sufficient for a landlord to deliver legal possession without actual possession?” GPT-4 responded:

Yes, there’s a distinction between legal possession and actual possession, and different jurisdictions handle this distinction differently.

- Legal Possession vs. Actual Possession:

- Legal Possession: Refers to the tenant’s right to possess a property. When a lease is signed (or an oral agreement is made, as long as it’s legally enforceable), the tenant typically gains legal possession of the property. This means that even if the tenant cannot actually use or occupy the property, they still have the legal rights to it.

- Actual Possession: Refers to the physical occupancy of a property. When a tenant moves into a property and starts using it, they have taken actual possession.

- Legal Possession Sufficient in Some Jurisdictions:

- In some jurisdictions, when a landlord grants a lease to a tenant, they are only obligated to deliver legal possession, not actual possession. In these jurisdictions, if a prior tenant holds over (i.e., doesn’t vacate at the end of their lease), the new tenant’s primary remedy might be against the holdover tenant, not the landlord. The reasoning is that the landlord has done their part by granting the right to possess the property, and any dispute over actual possession is between the new tenant and anyone unlawfully occupying the property.

- However, in many other jurisdictions, landlords have a duty to deliver both legal and actual possession. If they don’t, they can be in breach of the lease.

- Implication in the Given Scenario:

- If the jurisdiction in question is one where delivering legal possession is sufficient, then choice B (“The landlord had delivered the legal right of possession to the tenant.”) could be the correct reason for the court to find in favor of the landlord. In this scenario, the landlord gave the tenant the legal right to the property, and any issue with the holdover tenant would be for the new tenant to resolve.

- Variations by State:

- Landlord-tenant law can vary significantly from one state to another. So, it’s important to consult the specific laws and precedents of a given jurisdiction to understand the obligations and rights of both landlords and tenants.

If you are dealing with a specific state or jurisdiction, I can try to provide more detailed information about its stance on the delivery of possession.

I know that NCBE aims to test majority or consensus rules, rather than minority ones, on its exams, so I asked GPT-4 if it knew which rule (actual or legal possession) a majority of states follow. GPT-4 answered:

- In the U.S., the majority rule is that landlords are obligated to deliver actual possession of the premises to the tenant at the beginning of the lease term. If the landlord fails to do so, they can be held in breach of the lease.

- This rule is more protective of tenants, ensuring that when they sign a lease (or enter into a valid oral agreement for shorter-term tenancies) and perhaps move their belongings, business equipment, etc., they are assured of actually being able to use and occupy the space without interference from a holdover tenant or any other unauthorized occupant. After all, one of the primary reasons for entering into a lease is to have a physical space to live or conduct business.

- However, as with all legal matters, nuances can exist. While the majority rule requires actual possession, there are states or jurisdictions where only legal possession is required, and the burden is placed on the new tenant to deal with holdovers.

- But again, the majority trend leans toward requiring landlords to deliver actual possession. If you’re dealing with a specific issue or jurisdiction, it would be essential to consult local landlord-tenant statutes and case law or seek legal counsel for detailed guidance.

I know better than to trust GPT-4, which is trained on the internet rather than on legal databases, as an authoritative source on legal principles. In my previous posts, I have illustrated simply how GPT-4 could help a new lawyer identify legal issues in a client problem, understand the general scope of those issues, and generate questions to ask a client about the problem. I would not rely on GPT-4 to tell me whether a rule is the majority rule–or whether a particular state follows that rule.

So I turned to WestLaw to unravel this knotty question of whether a majority of states allow the landlord to deliver only legal possession to a tenant. WestLaw quickly confirmed that GPT-4 was correct. An ALR annotation collecting cases suggests that eleven states allow the landlord to deliver only legal possession, while twenty require the landlord to deliver actual possession together with legal possession. Two thoughtful student notes affirm that the requirement of actual possession is very much the majority rule, with one (Heiser) referring to a “mass exodus” away from the rule that legal possession suffices. (See the end of this post for citations.)

Even the state that originated the more landlord-friendly rule, New York, discarded it by statute in 1962. New York’s Real Property Law Article 7, section 233-a now provides: “In the absence of an express provision to the contrary, there shall be implied in every lease of real property a condition that the lessor will deliver possession at the beginning of the term.”

If you’ve followed me down this rabbit hole of real property law, you’ve learned: (1) At least for this rule of law, GPT-4 accurately identified the majority and minority rules. It was also able to explain those rules concisely. (2) NCBE is using, as one of the few sample questions it has released for the NextGen exam, a question that tests an outdated, minority rule. I alerted a contact at NCBE about this situation in mid-September, but the question is still on the sample questions site.

What do these lessons teach us about using AI in entry-law practice? And what do they suggest about the bar exam? I will explore both those questions in upcoming posts. Spoiler alert on the second question: It’s easy to declare, “ha, NCBE is wrong!” but the lesson I draw from this is deeper and more complex than that.

References:

Implied covenant or obligation to provide lessee with actual possession, 96 A.L.R.3d 1155 (Originally published in 1979, updated weekly).

Christopher Wm. Sullivan, Forgotten Lessons from the Common Law, the Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act, and the Holdover Tenant, 84 Wash. U.L. Rev. 1287 (2006).

Matthew J. Heiser, What’s Good for the Goose Isn’t Always Good for the Gander: The Inefficiencies of A Single Default Rule for Delivery of Possession of Leasehold Estates, 38 Colum. J.L. & Soc. Probs. 171 (2004).

AI, Bar Exam, GPT-4, NCBE No Comments YetThe Rule Against Perpetuities

We’ve known for a while that the July 2022 UBE included two (yes, two!) essays requiring detailed knowledge of the rule against perpetuities. NCBE has now released the essay questions from that exam, and I reviewed them today. Yes, there are two questions requiring knowledge of the rule against perpetuities–one question labelled “Trusts/Decedents’ Estates,” and the other labelled “Real Property.”

Most alarming, each question requires the exam-taker to recall a different version of the rule. The first question posits that the jurisdiction follows the common law rule against perpetuities; the second refers to the Uniform Statutory Rule Against Perpetuities.

Minimally competent lawyers do not need to recall from memory any version of the rule against perpetuities–much less two versions! A competent lawyer would recall that legal rules sometimes limit the power of property owners to restrict uses of property far into the future (that’s what I call a “threshold concept“) and would then research the law in their jurisdiction. Even if the lawyer had worked in the jurisdiction for 20 years, they would check the rule if they hadn’t applied it recently; rules change and this rule is too important (when it applies) to trust to memory.

Professors who still teach the rule against perpetuities might require their students to recall both versions of this rule for an end-of-semester exam. Memorization is one way to embed threshold concepts, although there are other methods (such as a deep understanding of the policies behind these concepts) that I find more effective. But there is no excuse for this type of memorization on a licensing exam that covers legal rules drawn from a dozen or more subjects.

Let’s hope this unfortunate exam redoubles NCBE’s commitment to limiting both the scope of the NextGen exam and the amount of memorization it will require. But even if that exam fulfills NCBE’s promises, it won’t debut until 2026. We need to reduce the amount of unproductive memorization required of exam-takers during the next three years. Two different versions of the rule against perpetuities? Really?

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, NCBE, Rule Against Perpetuities No Comments YetA Better Bar Exam—Look to Upper Canada?

Today, tens of thousands of aspiring lawyers across the United States sit for the bar exam in a ritual that should be designed to identify who has the ability to be a competent new lawyer. Yet a growing chorus of critics questions whether the current knowledge-focused exam is the best way to draw that line and protect the public. As Professor Deborah Merritt has noted, “On the one hand, the exam forces applicants to memorize hundreds of black-letter rules that they will never use in practice. On the other hand, the exam licenses lawyers who don’t know how to interview a client, compose an engagement letter, or negotiate with an adversary.”

For years, the response to critiques of the bar exam has been, in effect: “It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we can do if we want a psychometrically defensible exam.” The Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC), which governs the law licensing process for the province of Ontario, developed a licensing exam that calls that defense into question.

Overview of Law Society of Upper Canada Licensing Exam

The LSUC uses a 7-hour multiple-choice test consisting of 220 to 240 multiple-choice questions to test a wide range of competencies. For barristers (the litigating branch of the profession), that includes ethical and professional responsibilities; knowledge of the law; establishing and maintaining the lawyer-client relationship; problem/issue Identification, analysis, and assessment; alternative dispute resolution; litigation process; and practice management issues. A 2004 report explains how the LSUC identified key competencies and developed a licensing test based upon them.

Unlike the US exams, the LSUC exam is open-book, so it tests the ability to find and process relevant information rather than the ability to memorize rules. Most important, it tests a wider range of lawyering competencies than US exams, and it does so in the context of how lawyers address real client problems rather than as abstract analytical problems.

Below, we discuss how these differences address many of the critiques of the current US bar exams and make the LSUC exam an effective test of new lawyer competence. We also provide sample questions from both the LSUC and the US exam.

Open-Book Exam

Like all bar licensing exams in the United States (with the New Hampshire Daniel Webster Scholars Program as the sole exception), the LSUC exam is a pencil-and-paper timed exam. However, unlike any United States exam, including the Uniform Bar Exam, the LSUC licensing exam is open book.

The LSUC gives all candidates online access to materials that address all competencies the exam tests and encourages candidates to bring those materials to the exam. To help them navigate the materials, candidates are urged to create and bring to the exam tabbing or color-coding systems, short summaries of selected topics, index cards, and other study aids.

Lawyering is an open-book profession. Indeed, it might be considered malpractice to answer a legal problem without checking sources! As we have previously noted, good lawyers “…know enough to ask the right questions, figure out how to approach the problem and research the law, or know enough to recognize that the question is outside of their expertise and should be referred to a lawyer more well-versed in that area of law.” Actually referring a problem to someone else isn’t a feasible choice in the context of the bar exam, of course, but accessing the relevant knowledge base is.

The open-book LSUC exam tests a key lawyering competency untested by the US exam—the ability to find the appropriate legal information—and it addresses a significant critique of the current U.S. exams: that they test memorization of legal rules, a skill unrelated to actual law practice.

Candidates for the bar in Canada no doubt pore over the written material to learn the specifics, just as US students do, but they are also able to rely on that material to remind them of the rules as they answer the questions, just as a lawyer would do.

Testing More Lawyering Competencies

Like all bar exams in the US, the LSUC exam assesses legal knowledge and analytical skills. However, unlike US bar exams, the LSUC exam also assesses competencies that relate to fundamental lawyering skills beyond the ability to analyze legal doctrine.

As Professor Merritt has noted, studies conducted by the National Conference of Bar Examiners [NCBE] and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System confirm the gaps between the competencies new lawyers need and what the current US bar exams test, citing the absence of essential lawyering competencies such as interviewing principles; client communication; information gathering; case analysis and planning; alternative dispute resolution; negotiation; the litigation process; and practice management issues.

The NCBE has justified their absence by maintaining that such skills cannot be tested via multiple-choice questions. However, as illustrated below, the LSUC exam does just that, while also raising professional responsibility questions as part of the fact patterns testing those competencies.

Testing Competencies in Context of How Lawyers Use Information

The LSUC exam attempts to capture the daily work of lawyers. Rather than test knowledge of pure doctrine to predict a result as the US exams tend to do, the LSUC used Bloom’s taxonomy to develop questions that ask how knowledge of the law informs the proper representation of the client.

The LSUC questions seek information such as: what a client needs to know; how a lawyer would respond to a tribunal if asked “x”; where a lawyer would look to find the relevant information to determine the steps to be taken; and what issues a lawyer should research. That testing methodology replicates how lawyers use the law in practice much more effectively than do the US exams.

The LSUC exam format and content addresses a significant critique of US bar exams—that those exams ask questions that are unrelated to how lawyers use legal doctrine in practice and that the US exams fail to assess many of the key skills lawyers need.

Sample Questions from the LSUC and the MBE

Here is a sampling of LSUC questions that test for lawyering skills in a manner not addressed in US exams. These and other sample questions are available on the Law Society of Upper Canada’s website:

- Gertrude has come to Roberta, a lawyer, to draw up a power of attorney for personal care. Gertrude will be undergoing major surgery and wants to ensure that her wishes are fulfilled should anything go wrong. Gertrude’s husband is quite elderly and not in good health, so she may want her two adult daughters to be the attorneys. The religion of one of her daughters requires adherents to protect human life at all costs. Gertrude’s other daughter is struggling financially. What further information should Roberta obtain from Gertrude?

(b) The state of Gertrude’s marriage.

(c) Gertrude’s personal care wishes.

(d) Gertrude’s health status.

- Tracy was charged with Assault Causing Bodily Harm. She has instructed her lawyer, Kurt, to get her the fastest jury trial date possible. The Crown has not requested a preliminary inquiry. Kurt does not believe that a preliminary inquiry is necessary because of the quality of the disclosure. How can Kurt get Tracy the fastest trial date?

(b) Bring an 11(b) Application to force a quick jury trial date.

(c) Conduct the preliminary inquiry quickly and set down the jury trial.

(d) Elect on Tracy’s behalf trial by a Provincial Court Judge.

- Peyton, a real estate lawyer, is acting for a married couple, Lara and Chris, on the purchase of their first home. Lara’s mother will be lending the couple some money and would like to register a mortgage on title. Lara and Chris have asked Peyton to prepare and register the mortgage documentation. They are agreeable to Peyton acting for the three of them. Chris’ brother is also lending them money but Lara and Chris have asked Peyton not to tell Lara’s mother this fact. Should Peyton act?

(b) No, because there is a conflict of interest.

(c) Yes, because the parties are related.

(d) No, because she should not act on both the purchase and the mortgage.

- Prior to the real estate closing, in which jurisdiction should the purchaser’s lawyer search executions?

(b) Where the seller’s real property is located.

(c) Where the seller’s personal property is located.

(d) Where the seller is moving.

[These questions test the applicant’s understanding of: the information a lawyer needs from the client or other sources, strategic and effective use of trial process, ethical responsibilities, and knowledge of the real property registration system, all in the service of proper representation of a client. Correct answers: c, a, b, b.]

Compare these questions to typical MBE questions, which focus on applying memorized elements of legal rules to arrive at a conclusion about which party likely prevails. [More available here.]

- A woman borrowed $800,000 from a bank and gave the bank a note for that amount secured by a mortgage on her farm. Several years later, at a time when the woman still owed the bank $750,000 on the mortgage loan, she sold the farm to a man for $900,000. The man paid the woman $150,000 in cash and specifically assumed the mortgage note. The bank received notice of this transaction and elected not to exercise the optional due-on-sale clause in the mortgage. Without informing the man, the bank later released the woman from any further personal liability on the note. After he had owned the farm for a number of years, the man defaulted on the loan. The bank properly accelerated the loan, and the farm was eventually sold at a foreclosure sale for $500,000. Because there was still $600,000 owing on the note, the bank sued the man for the $100,000 deficiency. Is the man liable to the bank for the deficiency?

(b) No, because the bank’s release of the woman from personal liability also released the man.

(c) Yes, because the bank’s release of the woman constituted a clogging of the equity of redemption.

(d) Yes, because the man’s personal liability on the note was not affected by the bank’s release of the woman.

- A man arranged to have custom-made wooden shutters installed on the windows of his home. The contractor who installed the shutters did so by drilling screws and brackets into the exterior window frames and the shutters. The man later agreed to sell the home to a buyer. The sales agreement did not mention the shutters, the buyer did not inquire about them, and the buyer did not conduct a walkthrough inspection of the home before the closing. The man conveyed the home to the buyer by warranty deed. After the sale closed, the buyer noticed that the shutters and brackets had been removed from the home and that the window frames had been repaired and repainted. The buyer demanded that the man return the shutters and pay the cost of reinstallation, claiming that the shutters had been conveyed to him with the sale of the home. When the man refused, the buyer sued. Is the buyer likely to prevail?

(b) No, because the window frames had been repaired and repainted after removal of the shutters.

(c) Yes, because the shutters had become fixtures.

(d) Yes, because the man gave the buyer a warranty deed and the absence of the shutters violated a covenant of the deed

[Correct answers: d, c]

We Can Build a Better Bar Exam

As illustrated above, the LSUC exam shows that it is possible to test a far wider range of competencies than those tested in US bar exams.

Does the LSUC exam address all of the flaws of US bar exams? No—one problem that persists for both the LSUC and US exams is the requirement for rapid answers (less than 2 minutes per question), which rewards an ability and practice not associated with effective lawyering.

Does the LSUC exam fully address experiential skills? No—LSUC also requires applicants to “article” (a kind of apprenticeship with a law firm) or participate in the Law Practice Program (a four-month training course and a four-month work placement).

But the exam does what the NCBE has told us cannot be done. It is a psychometrically valid exam that assesses skills far beyond the competencies tested on US bar exams: skills such as interviewing, negotiating, counseling, fact investigation, and client-centered advocacy. And its emphasis is on lawyering competencies—using doctrine in the context of client problems.

Eileen Kaufman is Professor of Law at the Touro College, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center.

Andi Curcio is Professor of Law at the Georgia State University College of Law.

Carol Chomsky is Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School.

Higher Education, Bar Admissions, Bar Exam, Canada, LSUC, NCBE, The Law Society of Upper Canada, Uniform Bar Exam No Comments YetThe Latest Issue of the Bar Examiner

The National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) has released the March 2016 issue of their quarterly publication, the Bar Examiner. The issue includes annual statistics about bar passage rates, as well as several other articles. For those who lack time to read the issue, here are a few highlights:

Bar-Academy Relationships

In his Letter from the Chair, Judge Thomas Bice sounds a disappointingly hostile note towards law students. Quoting Justice Edward Chavez of the New Mexico Supreme Court, Bice suggests that “those who attend law school have come to have a sense of entitlement to the practice of law simply as a result of their education.” Against this sentiment, he continues, bar examiners “are truly the gatekeepers of this profession.” (P. 2)

NCBE President Erica Moeser, who has recently tangled with law school deans, offers a more conciliatory tone on her President’s Page. After noting the importance of the legal profession and the challenges facing law schools, she concludes: “In many ways, we are all in this together, and certainly all of us wish for better times.” (P. 5)

» Read the full text for The Latest Issue of the Bar Examiner

Data, Technology, Bar Exam, NCBE View Comment (1)ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

Almost a year has passed since the ill-fated July 2014 bar exam. As we approach that anniversary, the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) has offered a welcome update.

Mark Albanese, the organization’s Director of Testing and Research, recently acknowledged that: “The software used by many jurisdictions to allow their examinees to complete the written portion of the bar examination by computer experienced a glitch that could have stressed and panicked some examinees on the night before the MBE was administered.” This “glitch,” Albanese concedes, “cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor” to the decline in MBE scores and pass rates.

More important, Albanese offers compelling new evidence that ExamSoft played a major role in depressing July 2014 exam scores. He resists that conclusion, but I think the evidence speaks for itself. Let’s take a look at the new evidence, along with why this still matters.

LSAT Scores and MBE Scores

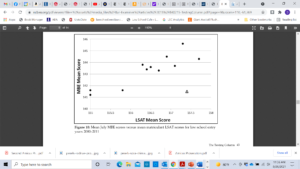

Albanese obtained the national mean LSAT score for law students who entered law school each year from 2000 through 2011. He then plotted those means against the average MBE scores earned by the same students three years later. The graph (Figure 10 on p. 43 of his article) looks like this:

As the black dots show, there is a strong linear relationship between scores on the LSAT and those for the MBE. Entering law school classes with high LSAT scores produce high MBE scores after graduation. For the classes that began law school from 2000 through 2010, the correlation is 0.89–a very high value.

Now look at the triangle toward the lower right-hand side of the graph. That symbol represents the relationship between mean LSAT score and mean MBE score for the class that entered law school in fall 2011 and took the bar exam in July 2014. As Albanese admits, this dot is way off the line: “it shows a mean MBE score that is much lower than that of other points with similar mean LSAT scores.”

Based on the historical relationship between LSAT and MBE scores, Albanese calculates that the Class of 2014 should have achieved a mean MBE score of 144.0. Instead, the mean was just 141.4, producing elevated bar failure rates across the country. As Albanese acknowledges, there was a clear “disruption in the relationship between the matriculant LSAT scores and MBE scores with the July 2014 examination.”

Professors Jerry Organ and Derek Muller made similar points last fall, but they were handicapped by their lack of access to LSAT means. The ABA releases only median scores, and those numbers are harder to compile into the type of persuasive graph that Albanese produced. Organ and Muller made an excellent case with their data–one that NCBE should have heeded–but they couldn’t be as precise as Albanese.

But now we have NCBE’s Director of Testing and Research admitting that “something happened” with the Class of 2014 “that disrupted the previous relationship between MBE scores and LSAT scores.” What could it have been?

Apprehending a Suspect

Albanese suggests a single culprit for the significant disruption shown in his graph: He states that the Law School Admission Council (LSAC) changed the manner in which it reported scores for students who take the LSAT more than once. Starting with the class that entered in fall 2011, Albanese writes, LSAC used the high score for each of those test takers; before then, it used the average scores.

At first blush, this seems like a possible explanation. On average, students who retake the LSAT improve their scores. Counting only high scores for these test takers, therefore, would increase the mean score for the entering class. National averages calculated using high scores for repeaters aren’t directly comparable to those computed with average scores.

But there is a problem with Albanese’s rationale: He is wrong about when LSAC switched its method for calculating national means. That occurred for the class that matriculated in fall 2010, not the one that entered in fall 2011. LSAC’s National Decision Profiles, which report these national means, state that quite clearly.

Albanese’s suspect, in other words, has an alibi. The change in LSAT reporting methods occurred a year earlier; it doesn’t explain the aberrational results on the July 2014 MBE. If we accept LSAT scores as a measure of ability, as NCBE has urged throughout this discussion, then the Class of 2014 should have received higher scores on the MBE. Why was their mean score so much lower than their LSAT test scores predicted?

NCBE has vigorously asserted that the test was not to blame; they prepared, vetted, and scored the July 2014 MBE using the same professional methods employed in the past. I believe them. Neither the test content nor the scoring algorithms are at fault. But we can’t ignore the evidence of Albanese’s graph: something untoward happened to the Class of 2014’s MBE scores.

The Villain

The villain almost certainly is the suspect who appeared at the very beginning of the story: ExamSoft. Anyone who has sat through the bar exam, who has talked to test-takers during those days, or who has watched students struggle to upload a single law school exam knows this.

I still remember the stress of the bar exam, although 35 years have passed. I’m pretty good at legal writing and analysis, but the exam wore me out. Few other experiences have taxed me as much mentally and physically as the bar exam.

For a majority of July 2014 test-takers, the ExamSoft “glitch” imposed hours of stress and sleeplessness in the middle of an already exhausting process. The disruption, moreover, occurred during the one period when examinees could recoup their energy and review material for the next day’s exam. It’s hard for me to imagine that ExamSoft’s failure didn’t reduce test-taker performance.

The numbers back up that claim. As I showed in a previous post, bar passage rates dropped significantly more in states affected directly by the software crash than in other states. The difference was large enough that there is less than a 0.001 probability that it occurred by chance. If we combine that fact with Albanese’s graph, what more evidence do we need?

Aiding and Abetting

ExamSoft was the original culprit, but NCBE aided and abetted the harm. The testing literature is clear that exams can be equated only if both the content and the test conditions are comparable. The testing conditions on July 29-30, 2014, were not the same as in previous years. The test-takers were stressed, overtired, and under-prepared because of ExamSoft’s disruption of the testing procedure.

NCBE was not responsible for the disruption, but it should have refrained from equating results produced under the 2014 conditions with those from previous years. Instead, it should have flagged this issue for state bar examiners and consulted with them about how to use scores that significantly understated the ability of test takers. The information was especially important for states that had not used ExamSoft, but whose examinees suffered repercussions through NCBE’s scaling process.

Given the strong relationship between LSAT scores and MBE performance, NCBE might even have used that correlation to generate a second set of scaled scores correcting for the ExamSoft disruption. States could have chosen which set of scores to use–or could have decided to make a one-time adjustment in the cut score. However states decided to respond, they would have understood the likely effect of the ExamSoft crisis on their examinees.

Instead, we have endured a year of obfuscation–and of blaming the Class of 2014 for being “less able” than previous classes. Albanese’s graph shows conclusively that diminished ability doesn’t explain the abnormal dip in July 2014 MBE scores. Our best predictor of that ability, scores earned on the LSAT, refutes that claim.

Lessons for the Future

It’s time to put the ExamSoft debacle to rest–although I hope we can do so with an even more candid acknowledgement from NCBE that the software crash was the primary culprit in this story. The test-takers deserve that affirmation.

At the same time, we need to reflect on what we can learn from this experience. In particular, why didn’t NCBE take the ExamSoft crash more seriously? Why didn’t NCBE and state bar examiners proactively address the impact of a serious flaw in exam administration? The equating and scaling process is designed to assure that exam takers do not suffer by taking one exam administration rather than another. The July 2014 examinees clearly did suffer by taking the exam during the ExamSoft disruption. Why didn’t NCBE and the bar examiners work to address that imbalance, rather than extend it?

I see three reasons. First, NCBE staff seem removed from the experience of bar exam takers. The psychometricians design and assess tests, but they are not lawyers. The president is a lawyer, but she was admitted through Wisconsin’s diploma privilege. NCBE staff may have tested bar questions and formats, but they lack firsthand knowledge of the test-taking experience. This may have affected their ability to grasp the impact of ExamSoft’s disruption.

Second, NCBE and law schools have competing interests. Law schools have economic and reputational interests in seeing their graduates pass the bar; NCBE has economic and reputational interests in disclaiming any disruption in the testing process. The bar examiners who work with NCBE have their own economic and reputational interests: reducing competition from new lawyers. Self interest is nothing to be ashamed of in a market economy; nor is self interest incompatible with working for the public good.

The problem with the bar exam, however, is that these parties (NCBE and bar examiners on one side, law schools on the other) tend to talk past one another. Rather than gain insights from each other, the parties often communicate after decisions are made. Each seems to believe that it protects the public interest, while the other is driven purely by self interest.

This stand-off hurts law school graduates, who get lost in the middle. NCBE and law schools need to start listening to one another; both sides have valid points to make. The ExamSoft crisis should have prompted immediate conversations between the groups. Law schools knew how the crash had affected their examinees; the cries of distress were loud and clear. NCBE knew, as Albanese’s graph shows, that MBE scores were far below outcomes predicted by the class’s LSAT scores. Discussion might have generated wisdom.

Finally, the ExamSoft debacle demonstrates that we need better coordination–and accountability–in the administration and scoring of bar exams. When law schools questioned the July 2014 results, NCBE’s president disclaimed any responsibility for exam administration. That’s technically true, but exam administration affects equating and scaling. Bar examiners, meanwhile, accepted NCBE’s results without question; they assumed that NCBE had taken all proper factors (including any effect from a flawed administration) into account.

We can’t rewind administration of the July 2014 bar exam; nor can we redo the scoring. But we can create a better system for exam administration going forward, one that includes more input from law schools (who have valid perspectives that NCBE and state bar examiners lack) as well as more coordination between NCBE and bar examiners on administration issues.

Jobs, Bar Exam, ExamSoft, NCBE View Comments (5)On the Bar Exam, My Graduates Are Your Graduates

It’s no secret that the qualifications of law students have declined since 2010. As applications fell, schools started dipping further into their applicant pools. LSAT scores offer one measure of this trend. Jerry Organ has summarized changes in those scores for the entering classes of 2010 through 2014. Based on Organ’s data, average LSAT scores for accredited law schools fell:

* 2.3 points at the 75th percentile

* 2.7 points at the median

* 3.4 points at the 25th percentile

Among other problems, this trend raises significant concerns about bar passage rates. Indeed, the President of the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) blamed the July 2014 drop in MBE scores on the fact that the Class of 2014 (which entered law school in 2011) was “less able” than earlier classes. I have suggested that the ExamSoft debacle contributed substantially to the score decline, but here I focus on the future. What will the drop in student quality mean for the bar exam?

Falling Bar Passage Rates

Most observers agree that bar passage rates are likely to fall over the coming years. Indeed, they may have already started that decline with the July 2014 and February 2015 exam administrations. I believe that the ExamSoft crisis and MBE content changes account for much of those slumps, but there is little doubt that bar passage rates will remain depressed and continue to fall.

A substantial part of the decline will stem from examinees with very low LSAT scores. Prior studies suggest that students with low scores (especially those with scores below 145) are at high risk of failing the bar. As the number of low-LSAT students increases at law schools, the number (and percentage) of bar failures probably will mount as well.

The impact, however, will not be limited just to those students. As I explained in a previous post, NCBE’s process of equating and scaling the MBE can drag down scores for all examinees when the group as a whole performs poorly. This occurs because the lower overall performance prompts NCBE to “scale down” MBE scores for all test-takers. Think of this as a kind of “reverse halo” effect, although it’s one that depends on mathematical formulas rather than subjective impressions.

State bar examiners, unfortunately, amplify the reverse-halo effect by the way in which they scale essay and MPT answers to MBE scores. I explain this process in a previous post. In brief, the MBE performance of each state’s examinees sets the curve for scoring other portions of the bar exam within that state. If Ohio’s 2015 examinees perform less well on the MBE than the 2013 group did, then the 2015 examinees will get lower essay and MPT scores as well.

The law schools that have admitted high-risk students, in sum, are not the only schools that will suffer lower bar passage rates. The processes of equating and scaling will depress scores for other examinees in the pool. The reductions may be small, but they will be enough to shift examinees near the passing score from one side to another. Test-takers who might have passed the bar in 2013 will not pass in 2015. In addition to taking a harder exam (i.e. a 7-subject MBE), these unfortunate examinees will suffer from the reverse-halo effect describe above.

On the bar exam, the performance of my graduates affects outcomes for your graduates. If my graduates perform less well than in previous years, fewer of your graduates will pass: my graduates are your graduates in this sense. The growing number of low-LSAT students attending Thomas Cooley and other schools will also affect the fate of our graduates. On the bar exam, Cooley’s graduates are our graduates.

Won’t NCBE Fix This?

NCBE should address this problem, but they have shown no signs of doing so. The equating/scaling process used by NCBE assumes that test-takers retain roughly the same proficiency from year to year. That assumption undergirds the equating process. Psychometricians recognize that, as abilities shift, equating becomes less reliable.* The recent decline in LSAT scores suggests that the proficiency of bar examinees will change markedly over the next few years. Under those circumstances, NCBE should not attempt to equate and scale raw scores; doing so risks the type of reverse-halo effect I have described.

The problem is particularly acute with the bar exam because scaling occurs at several points in the process. As proficiency declines, equating and scaling of MBE performance will inappropriately depress those scores. Those scores, in turn, will lower scores on the essay and MPT portions of the exam. The combined effect of these missteps is likely to produce noticeable–and undeserved–declines in scores for examinees who are just as qualified as those who passed the bar in previous years.

Remember that I’m not referring here to graduates who perform well below the passing score. If you believe that the bar exam is a proper measure of entry-level competence, then those test-takers deserve to fail. The problem is that an increased number of unqualified examinees will drag down scores for more able test-takers. Some of those scores will drop enough to push qualified examinees below the passing line.

Looking Ahead

NCBE, unfortunately, has not been responsive on issues related to their equating and scaling processes. It seems unlikely that the organization will address the problem described here. There is no doubt, meanwhile, that entry-level qualifications of law students have declined. If bar passage rates fall, as they almost surely will, it will be easy to blame all of the decline on less able graduates.

This leaves three avenues for concerned educators and policymakers:

1. Continue to press for more transparency and oversight of NCBE. Testing requires confidentiality, but safeguards are essential to protect individual examinees and public trust of the process.

2. Take a tougher stand against law schools with low bar passage rates. As professionals, we already have an obligation to protect aspirants to our ranks. Self interest adds a potent kick to that duty. As you view the qualifications of students matriculating at schools with low bar passage rates, remember: those matriculants will affect your school’s bar passage rate.

3. Push for alternative ways to measure attorney competence. New lawyers need to know basic doctrinal principles, and law schools should teach those principles. A closed-book, multiple-choice exam covering seven broad subject areas, however, is not a good measure of doctrinal knowledge. It is even worse when performance on that exam sets the curve for scores on other, more useful parts of the bar exam (such as the performance tests). And the situation is worse still when a single organization, with little oversight, controls scoring of that crucial multiple-choice exam.

I have some suggestions for how we might restructure the bar exam, but those ideas must wait for another post. For now, remember: On the bar exam, all graduates are your graduates.

* For a recent review of the literature on changing proficiencies, see Sonya Powers & Michael J. Kolen, Evaluating Equating Accuracy and Assumptions for Groups That Differ in Performance, 51 J. Educ. Measurement 39 (2014). A more reader-friendly overview is available in this online chapter (note particularly the statements on p. 274).

Data, Student Body, Teaching, Bar Exam, MBE, NCBE View Comments (6)ExamSoft Update

In a series of posts (here, here, and here) I’ve explained why I believe that ExamSoft’s massive computer glitch lowered performance on the July 2014 Multistate Bar Exam (MBE). I’ve also explained how NCBE’s equating and scaling process amplified the damage to produce a 5-point drop in the national bar passage rate.

We now have a final piece of evidence suggesting that something untoward happened on the July 2014 bar exam: The February 2015 MBE did not produce the same type of score drop. This February’s MBE was harder than any version of the test given over the last four decades; it covered seven subjects instead of six. Confronted with that challenge, the February scores declined somewhat from the previous year’s mark. The mean scaled score on the February 2015 MBE was 136.2, 1.8 points lower than the February 2014 mean scaled score of 138.0.

The contested July 2014 MBE, however, produced a drop of 2.8 points compared to the July 2013 test. That drop was 35.7% larger than the February drop. The July 2014 shift was also larger than any other year-to-year change (positive or negative) recorded during the last ten years. (I treat the February and July exams as separate categories, as NCBE and others do.)

The shift in February 2015 scores, on the other hand, is similar in magnitude to five other changes that occurred during the last decade. Scores dropped, but not nearly as much as in July–and that’s despite taking a harder version of the MBE. Why did the July 2014 examinees perform so poorly?

It can’t be a change in the quality of test takers, as NCBE’s president, Erica Moeser, has suggested in a series of communications to law deans and the profession. The February 2015 examinees started law school at about the same time as the July 2014 ones. As others have shown, law student credentials (as measured by LSAT scores) declined only modestly for students who entered law school in 2011.

We’re left with the conclusion that something very unusual happened in July 2014, and it’s not hard to find that unusual event: a software problem that occupied test-takers’ time, aggravated their stress, and interfered with their sleep.

On its own, my comparison of score drops does not show that the ExamSoft crisis caused the fall in July 2014 test performance. The other evidence I have already discussed is more persuasive. I offer this supplemental analysis for two reasons.

First, I want to forestall arguments that February’s performance proves that the July test-takers must have been less qualified than previous examinees. February’s mean scaled score did drop, compared to the previous February, but the drop was considerably less than the sharp July decline. The latter drop remains the largest score change during the last ten years. It clearly is an outlier that requires more explanation. (And this, of course, is without considering the increased difficulty of the February exam.)

Second, when combined with other evidence about the ExamSoft debacle, this comparison adds to the concerns. Why did scores fall so precipitously in July 2014? The answer seems to be ExamSoft, and we owe that answer to test-takers who failed the July 2014 bar exam.

One final note: Although I remain very concerned about both the handling of the ExamSoft problem and the equating of the new MBE to the old one, I am equally concerned about law schools that admit students who will struggle to pass a fairly administered bar exam. NCBE, state bar examiners, and law schools together stand as gatekeepers to the profession and we all owe a duty of fairness to those who seek to join the profession. More about that soon.

Technology, Bar Exam, ExamSoft, NCBE No Comments YetAbout Law School Cafe

Cafe Manager & Co-Moderator

Deborah J. Merritt

Cafe Designer & Co-Moderator

Kyle McEntee

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Around the Cafe

Subscribe

Categories

Recent Comments

- Law School Cafe on Scholarship Advice

- COVID Should Prompt Us To Get Rid Of New York’s Bar Exam Forever - The Lawyers Post on ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

- Targeted Legal Staffing Soluti on COVID-19 and the Bar Exam

- Advocates Denver on Women Law Students: Still Not Equal

- Douglas A. Berman on Ranking Academic Impact

Recent Posts

- The Bot Takes a Bow

- Fundamental Legal Concepts and Principles

- Lay Down the Law

- The Bot Updates the Bar Exam

- GPT-4 Beats the Bar Exam

Monthly Archives

Participate

Have something you think our audience would like to hear about? Interested in writing one or more guest posts? Send an email to the cafe manager at merritt52@gmail.com. We are interested in publishing posts from practitioners, students, faculty, and industry professionals.