The ABA’s New Bar Pass Rate Standards

Originally published on Above the Law.

Does the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar do enough to hold law schools accountable through accreditation? People throughout the legal profession, including people at law schools, think the answer is no.

This past weekend, the Section took an important step forward. The Section’s Standards Review Committee is charged with writing the law school accreditation standards, and it’s voted to send a slate of accountability measures to the Council of the Section of Legal Education — the final authority for law school accreditation.

This week’s column is about Standard 316 (the minimum bar passage standard) and Standard 509 (the transparency standard). Next week, I’ll write about the SRC’s proposals for refining the non-exploitation standard, Standard 501.

(more…)

» Read the full text for The ABA’s New Bar Pass Rate Standards

Data, Rules, ABA, ABA Section of Legal Education, Bar Exam, DPCC, Law School Transparency, Standard 316, Standard 509, Standards Review Committee No Comments YetWashington D.C. Adopts Uniform Bar Exam

Originally published on Above the Law.

Washington D.C. is the 20th jurisdiction to adopt the Uniform Bar Exam. In an order filed last Thursday, the D.C. Court of Appeals confirmed that it would begin administrating the exam this July.

This will not be the only new UBE jurisdiction in the coming weeks or months. Vermont’s Board of Bar Examiners also announced that “Vermont expects to adopt the Uniform Bar Examination for [the] July 2016 bar exam.” It’s not official but the Vermont Supreme Court asked the Board to propose rule changes to quickly make way for the changes.

(more…)

» Read the full text for Washington D.C. Adopts Uniform Bar Exam

Jobs, ABA, ABA Law Students Division, Bar Exam, Conference of Chief Justices, Uniform Bar Exam No Comments YetABA House to Vote on Uniform Bar Exam

Originally published on Above the Law.

Non-lawyers are encroaching on legal services traditionally offered by lawyers. Technology is changing how lawyers and clients think about value. Law schools have created a mismatch between the number of graduates and entry-level legal jobs. Throughout it all, regulators across the country are actively grappling (and griping) about how best to address these extraordinary circumstances.

While proposed actions or inactions cause sharp disagreements around the country about how to move the profession forward in the 21st century, one common-sense action shouldn’t: adopting the Uniform Bar Exam. Next Monday, the ABA’s House of Delegates will consider a resolution from the ABA’s Law Student Division that calls for all jurisdictions to adopt this portable exam. The House should support this measure, and all jurisdictions should adopt the UBE as quickly as possible.

(more…)

» Read the full text for ABA House to Vote on Uniform Bar Exam

Rules, Student Costs, ABA, ABA Law Students Division, ABA Section of Legal Education, Bar Exam, Uniform Bar Exam View Comment (1)Experiential Education and Bar Passage

Robert Kuehn has written an excellent post about clinical courses and bar passage. He notes that Erica Moeser, President of the National Conference of Bar Examiners, suggested in print that declining bar passage rates might stem in part from the rise of experiential learning in law schools. NCBE’s Director of Testing and Research has made the same claim, noting that: “There has also been a trend toward incorporating non-core courses and clinical experiences into the law school curriculum. These, too, can take students’ time away from learning the core concepts that are tested on the bar examination.”

When Kuehn contacted Moeser to ask if she knew about any empirical research supporting this purported connection, she admitted that she knew of none. Nor did her testing staff. (more…)

» Read the full text for Experiential Education and Bar Passage

Teaching, Bar Exam, Erica Moeser, Experiential Courses No Comments YetCorrected Post on July Exam Results

[To replace my post from yesterday, which misreported Oklahoma’s pass rate]

States have started to release results from the July 2015 bar exam. So far the results I have seen are mixed:

Iowa’s first-time takers enjoyed a significant increase in the pass rate, from 82% in July 2014 to 91% in July 2015. (I draw all 2014 statistics in this post from NCBE data).

New Mexico’s first-timers, on the other hand, suffered a substantial decline in their pass rate: 88% passed in July 2014 while just 76% did in July 2015.

In Missouri, the pass rate for first-timers fell slightly, from 88% in July 2014 to 87% in July 2015.

Two other states have released statistics for all test-takers, without identifying first-timers. In one of those, Oklahoma, the pass rate fell substantially–from 79% to 68%. In the other, Washington state, the rate was relatively stable at 77% in July 2014 and 76% in 2015.

A few other states have released individual results, but have not yet published pass rates. It may be possible to calculate overall pass rates in those states, but I haven’t tried to do so; first-time pass rates provide a more reliable year-to-year measure, so it is worth waiting for those.

Predictions

I suggest that bar results will continue to be mixed, due to three cross-cutting factors:

1. The July 2015 exam was not marred by the ExamSoft debacle. This factor will push 2015 passing rates up above 2014 ones.

2. The July 2015 MBE includes seven subjects rather than six. The more difficult exam will push passing rates down for 2015.

3. The qualifications of examinees, as measured by their entering LSAT scores, declined between the Class of 2014 and Class of 2015. This factor will also push passing rates down.

Overall, I expect pass rates to decline between July 2014 and July 2015; the second and third factors are strong ones. A contrary trend in a few states like Iowa, however, may underscore the effects of last year’s ExamSoft crisis. Once all results are available, more detailed analysis may show the relative influence of the three factors listed above.

Student Body, Bar Exam, ExamSoft View Comments (2)ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

Almost a year has passed since the ill-fated July 2014 bar exam. As we approach that anniversary, the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) has offered a welcome update.

Mark Albanese, the organization’s Director of Testing and Research, recently acknowledged that: “The software used by many jurisdictions to allow their examinees to complete the written portion of the bar examination by computer experienced a glitch that could have stressed and panicked some examinees on the night before the MBE was administered.” This “glitch,” Albanese concedes, “cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor” to the decline in MBE scores and pass rates.

More important, Albanese offers compelling new evidence that ExamSoft played a major role in depressing July 2014 exam scores. He resists that conclusion, but I think the evidence speaks for itself. Let’s take a look at the new evidence, along with why this still matters.

LSAT Scores and MBE Scores

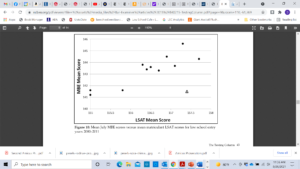

Albanese obtained the national mean LSAT score for law students who entered law school each year from 2000 through 2011. He then plotted those means against the average MBE scores earned by the same students three years later. The graph (Figure 10 on p. 43 of his article) looks like this:

As the black dots show, there is a strong linear relationship between scores on the LSAT and those for the MBE. Entering law school classes with high LSAT scores produce high MBE scores after graduation. For the classes that began law school from 2000 through 2010, the correlation is 0.89–a very high value.

Now look at the triangle toward the lower right-hand side of the graph. That symbol represents the relationship between mean LSAT score and mean MBE score for the class that entered law school in fall 2011 and took the bar exam in July 2014. As Albanese admits, this dot is way off the line: “it shows a mean MBE score that is much lower than that of other points with similar mean LSAT scores.”

Based on the historical relationship between LSAT and MBE scores, Albanese calculates that the Class of 2014 should have achieved a mean MBE score of 144.0. Instead, the mean was just 141.4, producing elevated bar failure rates across the country. As Albanese acknowledges, there was a clear “disruption in the relationship between the matriculant LSAT scores and MBE scores with the July 2014 examination.”

Professors Jerry Organ and Derek Muller made similar points last fall, but they were handicapped by their lack of access to LSAT means. The ABA releases only median scores, and those numbers are harder to compile into the type of persuasive graph that Albanese produced. Organ and Muller made an excellent case with their data–one that NCBE should have heeded–but they couldn’t be as precise as Albanese.

But now we have NCBE’s Director of Testing and Research admitting that “something happened” with the Class of 2014 “that disrupted the previous relationship between MBE scores and LSAT scores.” What could it have been?

Apprehending a Suspect

Albanese suggests a single culprit for the significant disruption shown in his graph: He states that the Law School Admission Council (LSAC) changed the manner in which it reported scores for students who take the LSAT more than once. Starting with the class that entered in fall 2011, Albanese writes, LSAC used the high score for each of those test takers; before then, it used the average scores.

At first blush, this seems like a possible explanation. On average, students who retake the LSAT improve their scores. Counting only high scores for these test takers, therefore, would increase the mean score for the entering class. National averages calculated using high scores for repeaters aren’t directly comparable to those computed with average scores.

But there is a problem with Albanese’s rationale: He is wrong about when LSAC switched its method for calculating national means. That occurred for the class that matriculated in fall 2010, not the one that entered in fall 2011. LSAC’s National Decision Profiles, which report these national means, state that quite clearly.

Albanese’s suspect, in other words, has an alibi. The change in LSAT reporting methods occurred a year earlier; it doesn’t explain the aberrational results on the July 2014 MBE. If we accept LSAT scores as a measure of ability, as NCBE has urged throughout this discussion, then the Class of 2014 should have received higher scores on the MBE. Why was their mean score so much lower than their LSAT test scores predicted?

NCBE has vigorously asserted that the test was not to blame; they prepared, vetted, and scored the July 2014 MBE using the same professional methods employed in the past. I believe them. Neither the test content nor the scoring algorithms are at fault. But we can’t ignore the evidence of Albanese’s graph: something untoward happened to the Class of 2014’s MBE scores.

The Villain

The villain almost certainly is the suspect who appeared at the very beginning of the story: ExamSoft. Anyone who has sat through the bar exam, who has talked to test-takers during those days, or who has watched students struggle to upload a single law school exam knows this.

I still remember the stress of the bar exam, although 35 years have passed. I’m pretty good at legal writing and analysis, but the exam wore me out. Few other experiences have taxed me as much mentally and physically as the bar exam.

For a majority of July 2014 test-takers, the ExamSoft “glitch” imposed hours of stress and sleeplessness in the middle of an already exhausting process. The disruption, moreover, occurred during the one period when examinees could recoup their energy and review material for the next day’s exam. It’s hard for me to imagine that ExamSoft’s failure didn’t reduce test-taker performance.

The numbers back up that claim. As I showed in a previous post, bar passage rates dropped significantly more in states affected directly by the software crash than in other states. The difference was large enough that there is less than a 0.001 probability that it occurred by chance. If we combine that fact with Albanese’s graph, what more evidence do we need?

Aiding and Abetting

ExamSoft was the original culprit, but NCBE aided and abetted the harm. The testing literature is clear that exams can be equated only if both the content and the test conditions are comparable. The testing conditions on July 29-30, 2014, were not the same as in previous years. The test-takers were stressed, overtired, and under-prepared because of ExamSoft’s disruption of the testing procedure.

NCBE was not responsible for the disruption, but it should have refrained from equating results produced under the 2014 conditions with those from previous years. Instead, it should have flagged this issue for state bar examiners and consulted with them about how to use scores that significantly understated the ability of test takers. The information was especially important for states that had not used ExamSoft, but whose examinees suffered repercussions through NCBE’s scaling process.

Given the strong relationship between LSAT scores and MBE performance, NCBE might even have used that correlation to generate a second set of scaled scores correcting for the ExamSoft disruption. States could have chosen which set of scores to use–or could have decided to make a one-time adjustment in the cut score. However states decided to respond, they would have understood the likely effect of the ExamSoft crisis on their examinees.

Instead, we have endured a year of obfuscation–and of blaming the Class of 2014 for being “less able” than previous classes. Albanese’s graph shows conclusively that diminished ability doesn’t explain the abnormal dip in July 2014 MBE scores. Our best predictor of that ability, scores earned on the LSAT, refutes that claim.

Lessons for the Future

It’s time to put the ExamSoft debacle to rest–although I hope we can do so with an even more candid acknowledgement from NCBE that the software crash was the primary culprit in this story. The test-takers deserve that affirmation.

At the same time, we need to reflect on what we can learn from this experience. In particular, why didn’t NCBE take the ExamSoft crash more seriously? Why didn’t NCBE and state bar examiners proactively address the impact of a serious flaw in exam administration? The equating and scaling process is designed to assure that exam takers do not suffer by taking one exam administration rather than another. The July 2014 examinees clearly did suffer by taking the exam during the ExamSoft disruption. Why didn’t NCBE and the bar examiners work to address that imbalance, rather than extend it?

I see three reasons. First, NCBE staff seem removed from the experience of bar exam takers. The psychometricians design and assess tests, but they are not lawyers. The president is a lawyer, but she was admitted through Wisconsin’s diploma privilege. NCBE staff may have tested bar questions and formats, but they lack firsthand knowledge of the test-taking experience. This may have affected their ability to grasp the impact of ExamSoft’s disruption.

Second, NCBE and law schools have competing interests. Law schools have economic and reputational interests in seeing their graduates pass the bar; NCBE has economic and reputational interests in disclaiming any disruption in the testing process. The bar examiners who work with NCBE have their own economic and reputational interests: reducing competition from new lawyers. Self interest is nothing to be ashamed of in a market economy; nor is self interest incompatible with working for the public good.

The problem with the bar exam, however, is that these parties (NCBE and bar examiners on one side, law schools on the other) tend to talk past one another. Rather than gain insights from each other, the parties often communicate after decisions are made. Each seems to believe that it protects the public interest, while the other is driven purely by self interest.

This stand-off hurts law school graduates, who get lost in the middle. NCBE and law schools need to start listening to one another; both sides have valid points to make. The ExamSoft crisis should have prompted immediate conversations between the groups. Law schools knew how the crash had affected their examinees; the cries of distress were loud and clear. NCBE knew, as Albanese’s graph shows, that MBE scores were far below outcomes predicted by the class’s LSAT scores. Discussion might have generated wisdom.

Finally, the ExamSoft debacle demonstrates that we need better coordination–and accountability–in the administration and scoring of bar exams. When law schools questioned the July 2014 results, NCBE’s president disclaimed any responsibility for exam administration. That’s technically true, but exam administration affects equating and scaling. Bar examiners, meanwhile, accepted NCBE’s results without question; they assumed that NCBE had taken all proper factors (including any effect from a flawed administration) into account.

We can’t rewind administration of the July 2014 bar exam; nor can we redo the scoring. But we can create a better system for exam administration going forward, one that includes more input from law schools (who have valid perspectives that NCBE and state bar examiners lack) as well as more coordination between NCBE and bar examiners on administration issues.

Jobs, Bar Exam, ExamSoft, NCBE View Comments (5)ExamSoft Settlement

A federal judge has tentatively approved settlement of consolidated class action lawsuits brought by July 2014 bar examinees against ExamSoft. The lawsuits arose out of the well known difficulties that test-takers experienced when they tried to upload their essay answers through ExamSoft’s software. I have written about this debacle, and its likely impact on bar scores, several times. For the most recent post in the series, see here.

Looking at this settlement, it’s hard to know what the class representatives were thinking. Last summer, examinees paid between $100 and $150 for the privilege of using ExamSoft software. When the uploads failed to work, they were unable to reach ExamSoft’s customer service lines. Many endured hours of anxiety as they tried to upload their exams or contact customer service. The snafu distracted them preparing for the next day’s exam or getting some much needed sleep.

What are the examinees who suffered through this “barmageddon” getting for their troubles? $90 apiece. That’s right, they’re not even getting a full refund on the fees they paid. The class action lawyers, meanwhile, will walk away with up to $600,000 in attorneys’ fees.

I understand that damages for emotional distress aren’t awarded in contract actions. I get that (and hopefully got that right on the MBE). But agreeing to a settlement that awards less than the amount exam takers paid for this shoddy service? ExamSoft clearly failed to perform its side of the bargain; the complaint stated a very straightforward claim for breach of contract. In addition, the plaintiffs invoked federal and state consumer laws that might have awarded other relief.

What were the class representatives thinking? Perhaps they used the lawsuit as a training ground to enter the apparently lucrative field of representing other plaintiffs in class action suits. Now that they know how to collect handsome fees, they’re not worried about the pocket change they paid to ExamSoft.

I believe in class actions–they’re a necessary procedure to enforce some claims, including the ones asserted in this case. But the field now suffers from so much abuse, with attorneys collecting the lions’ share of awards and class members receiving relatively little. It’s no wonder that the public, and some appellate courts, have become so cynical about class actions.

From that perspective, there’s a great irony in this settlement. People who wanted to be lawyers, and who suffered a compensable breach of contract while engaged in that quest, have now been shortchanged by the very professionals they seek to join.

Technology, Bar Exam, ExamSoft No Comments YetOn the Bar Exam, My Graduates Are Your Graduates

It’s no secret that the qualifications of law students have declined since 2010. As applications fell, schools started dipping further into their applicant pools. LSAT scores offer one measure of this trend. Jerry Organ has summarized changes in those scores for the entering classes of 2010 through 2014. Based on Organ’s data, average LSAT scores for accredited law schools fell:

* 2.3 points at the 75th percentile

* 2.7 points at the median

* 3.4 points at the 25th percentile

Among other problems, this trend raises significant concerns about bar passage rates. Indeed, the President of the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) blamed the July 2014 drop in MBE scores on the fact that the Class of 2014 (which entered law school in 2011) was “less able” than earlier classes. I have suggested that the ExamSoft debacle contributed substantially to the score decline, but here I focus on the future. What will the drop in student quality mean for the bar exam?

Falling Bar Passage Rates

Most observers agree that bar passage rates are likely to fall over the coming years. Indeed, they may have already started that decline with the July 2014 and February 2015 exam administrations. I believe that the ExamSoft crisis and MBE content changes account for much of those slumps, but there is little doubt that bar passage rates will remain depressed and continue to fall.

A substantial part of the decline will stem from examinees with very low LSAT scores. Prior studies suggest that students with low scores (especially those with scores below 145) are at high risk of failing the bar. As the number of low-LSAT students increases at law schools, the number (and percentage) of bar failures probably will mount as well.

The impact, however, will not be limited just to those students. As I explained in a previous post, NCBE’s process of equating and scaling the MBE can drag down scores for all examinees when the group as a whole performs poorly. This occurs because the lower overall performance prompts NCBE to “scale down” MBE scores for all test-takers. Think of this as a kind of “reverse halo” effect, although it’s one that depends on mathematical formulas rather than subjective impressions.

State bar examiners, unfortunately, amplify the reverse-halo effect by the way in which they scale essay and MPT answers to MBE scores. I explain this process in a previous post. In brief, the MBE performance of each state’s examinees sets the curve for scoring other portions of the bar exam within that state. If Ohio’s 2015 examinees perform less well on the MBE than the 2013 group did, then the 2015 examinees will get lower essay and MPT scores as well.

The law schools that have admitted high-risk students, in sum, are not the only schools that will suffer lower bar passage rates. The processes of equating and scaling will depress scores for other examinees in the pool. The reductions may be small, but they will be enough to shift examinees near the passing score from one side to another. Test-takers who might have passed the bar in 2013 will not pass in 2015. In addition to taking a harder exam (i.e. a 7-subject MBE), these unfortunate examinees will suffer from the reverse-halo effect describe above.

On the bar exam, the performance of my graduates affects outcomes for your graduates. If my graduates perform less well than in previous years, fewer of your graduates will pass: my graduates are your graduates in this sense. The growing number of low-LSAT students attending Thomas Cooley and other schools will also affect the fate of our graduates. On the bar exam, Cooley’s graduates are our graduates.

Won’t NCBE Fix This?

NCBE should address this problem, but they have shown no signs of doing so. The equating/scaling process used by NCBE assumes that test-takers retain roughly the same proficiency from year to year. That assumption undergirds the equating process. Psychometricians recognize that, as abilities shift, equating becomes less reliable.* The recent decline in LSAT scores suggests that the proficiency of bar examinees will change markedly over the next few years. Under those circumstances, NCBE should not attempt to equate and scale raw scores; doing so risks the type of reverse-halo effect I have described.

The problem is particularly acute with the bar exam because scaling occurs at several points in the process. As proficiency declines, equating and scaling of MBE performance will inappropriately depress those scores. Those scores, in turn, will lower scores on the essay and MPT portions of the exam. The combined effect of these missteps is likely to produce noticeable–and undeserved–declines in scores for examinees who are just as qualified as those who passed the bar in previous years.

Remember that I’m not referring here to graduates who perform well below the passing score. If you believe that the bar exam is a proper measure of entry-level competence, then those test-takers deserve to fail. The problem is that an increased number of unqualified examinees will drag down scores for more able test-takers. Some of those scores will drop enough to push qualified examinees below the passing line.

Looking Ahead

NCBE, unfortunately, has not been responsive on issues related to their equating and scaling processes. It seems unlikely that the organization will address the problem described here. There is no doubt, meanwhile, that entry-level qualifications of law students have declined. If bar passage rates fall, as they almost surely will, it will be easy to blame all of the decline on less able graduates.

This leaves three avenues for concerned educators and policymakers:

1. Continue to press for more transparency and oversight of NCBE. Testing requires confidentiality, but safeguards are essential to protect individual examinees and public trust of the process.

2. Take a tougher stand against law schools with low bar passage rates. As professionals, we already have an obligation to protect aspirants to our ranks. Self interest adds a potent kick to that duty. As you view the qualifications of students matriculating at schools with low bar passage rates, remember: those matriculants will affect your school’s bar passage rate.

3. Push for alternative ways to measure attorney competence. New lawyers need to know basic doctrinal principles, and law schools should teach those principles. A closed-book, multiple-choice exam covering seven broad subject areas, however, is not a good measure of doctrinal knowledge. It is even worse when performance on that exam sets the curve for scores on other, more useful parts of the bar exam (such as the performance tests). And the situation is worse still when a single organization, with little oversight, controls scoring of that crucial multiple-choice exam.

I have some suggestions for how we might restructure the bar exam, but those ideas must wait for another post. For now, remember: On the bar exam, all graduates are your graduates.

* For a recent review of the literature on changing proficiencies, see Sonya Powers & Michael J. Kolen, Evaluating Equating Accuracy and Assumptions for Groups That Differ in Performance, 51 J. Educ. Measurement 39 (2014). A more reader-friendly overview is available in this online chapter (note particularly the statements on p. 274).

Data, Student Body, Teaching, Bar Exam, MBE, NCBE View Comments (6)New York Adopts the Uniform Bar Exam

New York’s highest court announced today that it will begin administering the Uniform Bar Exam (UBE) in July 2016. In addition to passing the two-day UBE, applicants will have to complete an online course about NY law and pass an online exam based on that content.

New York’s move almost certainly will prompt other states to follow suit. Within a few years, we are likely to have a national bar exam. What will this mean for new lawyers? I offer some initial thoughts below.

Positives

1. The Uniform Bar Exam increases mobility for new lawyers. Passing the UBE in one state does not guarantee admission in a different state, because states can select different passing scores. States may also require applicants to complete a state-specific exam. The UBE, however, greatly eases interstate migration for newly admitted lawyers. This is particularly important in a tight job market.

[Adoption of the UBE doesn’t matter as much for experienced lawyers, because most states allow lawyers to “waive in” to their bar after five years of experience in another jurisdiction.]

2. This increased mobility is especially important to women lawyers. My study of new lawyers admitted to the Ohio bar in 2010 found that women were significantly more likely than men to move out of state within their first five years of practice. Almost one fifth of the women (18.4%) left Ohio after gaining bar admission, while just 14.1% of the men did so.

3. By testing general principles, rather than the law of a particular state, the UBE better fits the material that students cover in law school. Students may have to spend somewhat less time preparing for the bar. Even if a state tests separately on local law, as NY plans to do, that testing will occur at a different time.

4. The National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE), which creates all portions of the UBE, is a large organization with the resources to develop and pretest sensible questions. Its essay questions may be more fair than ones developed by state bar examiners.

Negatives

On the other hand, there are several drawbacks to the UBE. As a long-time supporter of a national bar exam, I am more troubled by these issues than I once thought I would be:

1. Although mobile lawyers will benefit from the UBE’s portability, those who remain in-state will have to jump more hurdles than ever to gain bar admission. On top of a two-day bar exam, they will have to complete an online course about NY law and pass a 50-question multiple-choice test on that law. Our school’s director of bar support, who has coached students taking the NY bar, says that the NY multiple-choice test is no picnic.

2. Bar passage could become even more onerous if NY adds an experiential component to its testing. The advisory committee that endorsed adoption of the UBE also recommended creation of a new “task force to study whether experiential learning may be quantified as a licensing requirement or whether some other demonstration of skills acquisition should be required for licensing.” I like the idea of measuring practice skills before bar admission, but I would replace some of our written exams with the experiential component. Adding yet another layer to proficiency testing imposes burdens on new lawyers that more senior ones did not face.

3. Multiple-choice questions make up half the UBE score, a higher proportion than some states currently allot to those questions. Multiple-choice questions have their place, but I would rather test new lawyers on performance tasks like those in the MPT. To me, the MBE is even further removed from practice realities than any law school exam. A closed-book exam covering seven different, very broad subject areas does little but test an applicant’s ability to cram large amounts of material into memory.

4. In addition to my general concern about multiple-choice bar exams, some bar studies find that women (on average) score slightly higher than men on essay questions and performance items, while men (on average) score slightly higher on the MBE. When the MBE accounts for 35% (California) or 40% (Texas) of the exam, these differences balance out, creating virtually identical pass rates for men and women. Is it appropriate to increase the weight accorded multiple-choice items if we know that this shift is likely to favor one gender?

5. NCBE was remarkably unresponsive in dealing with the possible impact of last summer’s ExamSoft meltdown. The organization has also become less transparent, withholding information (such as raw scores) that it used to disclose. Concentrating even more power in one organization is risky. Who will hold NCBE accountable? What pressure will it feel to maintain high-quality services?

Other Thoughts

I continue to consider the advantages and disadvantages of NY’s move to the UBE, and will update this post as other points emerge. Please add your own thoughts in the comments. A national bar exam seems long overdue, but aspects of this shift concern me. As other states react to NY’s move, can we find ways to preserve the advantages of a national bar exam while assuring that (a) the exam tests proficiencies and knowledge that matter; (b) the exam does not create additional burdens for bar applicants; and (c) there is appropriate oversight of the organization administering the exam?

Jobs, Rules, Bar Exam, UBE No Comments YetExamSoft Update

In a series of posts (here, here, and here) I’ve explained why I believe that ExamSoft’s massive computer glitch lowered performance on the July 2014 Multistate Bar Exam (MBE). I’ve also explained how NCBE’s equating and scaling process amplified the damage to produce a 5-point drop in the national bar passage rate.

We now have a final piece of evidence suggesting that something untoward happened on the July 2014 bar exam: The February 2015 MBE did not produce the same type of score drop. This February’s MBE was harder than any version of the test given over the last four decades; it covered seven subjects instead of six. Confronted with that challenge, the February scores declined somewhat from the previous year’s mark. The mean scaled score on the February 2015 MBE was 136.2, 1.8 points lower than the February 2014 mean scaled score of 138.0.

The contested July 2014 MBE, however, produced a drop of 2.8 points compared to the July 2013 test. That drop was 35.7% larger than the February drop. The July 2014 shift was also larger than any other year-to-year change (positive or negative) recorded during the last ten years. (I treat the February and July exams as separate categories, as NCBE and others do.)

The shift in February 2015 scores, on the other hand, is similar in magnitude to five other changes that occurred during the last decade. Scores dropped, but not nearly as much as in July–and that’s despite taking a harder version of the MBE. Why did the July 2014 examinees perform so poorly?

It can’t be a change in the quality of test takers, as NCBE’s president, Erica Moeser, has suggested in a series of communications to law deans and the profession. The February 2015 examinees started law school at about the same time as the July 2014 ones. As others have shown, law student credentials (as measured by LSAT scores) declined only modestly for students who entered law school in 2011.

We’re left with the conclusion that something very unusual happened in July 2014, and it’s not hard to find that unusual event: a software problem that occupied test-takers’ time, aggravated their stress, and interfered with their sleep.

On its own, my comparison of score drops does not show that the ExamSoft crisis caused the fall in July 2014 test performance. The other evidence I have already discussed is more persuasive. I offer this supplemental analysis for two reasons.

First, I want to forestall arguments that February’s performance proves that the July test-takers must have been less qualified than previous examinees. February’s mean scaled score did drop, compared to the previous February, but the drop was considerably less than the sharp July decline. The latter drop remains the largest score change during the last ten years. It clearly is an outlier that requires more explanation. (And this, of course, is without considering the increased difficulty of the February exam.)

Second, when combined with other evidence about the ExamSoft debacle, this comparison adds to the concerns. Why did scores fall so precipitously in July 2014? The answer seems to be ExamSoft, and we owe that answer to test-takers who failed the July 2014 bar exam.

One final note: Although I remain very concerned about both the handling of the ExamSoft problem and the equating of the new MBE to the old one, I am equally concerned about law schools that admit students who will struggle to pass a fairly administered bar exam. NCBE, state bar examiners, and law schools together stand as gatekeepers to the profession and we all owe a duty of fairness to those who seek to join the profession. More about that soon.

Technology, Bar Exam, ExamSoft, NCBE No Comments YetAbout Law School Cafe

Cafe Manager & Co-Moderator

Deborah J. Merritt

Cafe Designer & Co-Moderator

Kyle McEntee

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Around the Cafe

Subscribe

Categories

Recent Comments

- websites on Experiential Education

- Law School Cafe on Scholarship Advice

- COVID Should Prompt Us To Get Rid Of New York’s Bar Exam Forever - The Lawyers Post on ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

- Targeted Legal Staffing Soluti on COVID-19 and the Bar Exam

- Advocates Denver on Women Law Students: Still Not Equal

Recent Posts

- Experiential Education

- The Bot Takes a Bow

- Fundamental Legal Concepts and Principles

- Lay Down the Law

- The Bot Updates the Bar Exam

Monthly Archives

Participate

Have something you think our audience would like to hear about? Interested in writing one or more guest posts? Send an email to the cafe manager at merritt52@gmail.com. We are interested in publishing posts from practitioners, students, faculty, and industry professionals.