Stephen Carter on the Bar Exam

Eminent Yale Professor Stephen Carter has penned a thoughtful critique of the bar exam. Professor Carter notes the exam’s similarities to the LSAT, which some law schools have abandoned as an admissions requirement. In addition to their shared affection for multiple choice questions, the LSAT and bar exam both constrain the diversity of our profession. Despite the bar exam’s disproportionate racial impact, Professor Carter notes, the exam has never been properly validated. Here, he cites a column I wrote in 2017 for the AALS Newsletter.

As I wrote then, state bar examiners and NCBE designed the bar exam around a definition of minimum competence that they “felt in their bones.” NCBE did not conduct a practice analysis of the knowledge and skills that new lawyers need until 2012. That analysis supported some of the doctrinal subjects that NCBE was testing, but not the depth of memorization required by the exam. The analysis also confirmed that skills like researching the law, fact gathering, negotiating, and interviewing were essential for law practice–all skills conspicuously absent from the bar exam.

NCBE conducted another practice analysis in 2019, which once again exposed numerous flaws in the exam. My own research, conducted with Logan Cornett and IAALS (the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System), reached a similar conclusion: the written bar exam tests both too much and too little. It restricts admission to the profession (especially of people of color) without adequately protecting the public.

NCBE is developing a new exam that will better serve the goals of licensing, but that exam won’t be ready until 2026. And it may still demand more memorization than new lawyers need while omitting critical skills like legal research. Lawyers don’t memorize the millions of state, local, and national rules that govern our society; they master threshold concepts and research techniques that allow them to find the rules they need. No matter how improved, NCBE’s bar exam is likely to remain an artificial barrier to entry into the legal profession.

How else can we license lawyers? Professor Carter suggests wider use of Wisconsin’s diploma privilege–licensing all graduates of ABA-accredited law schools. Here I part ways with him. If law schools taught law students all of the ways they need to think like a lawyer, I might agree. But most law schools persist in the illusion that 3 years of reading judicial opinions (or, for many students, 1-2 semesters of reading judicial opinions followed by 4-5 semesters of downloading case squibs and course outlines from Quimbee and other sources) teaches students to “think like lawyers.”

The traditional law school curriculum shies away from the more complex thinking required to gather facts related to legal principles, interview clients and witnesses, negotiate letter matters, and counsel clients. Law school classes teach students two-dimensional thinking, while law practice requires thinking in four dimensions.

Fortunately, it is possible to improve both legal education and licensing by adopting an experiential education path to licensing. New Hampshire adopted this approach through its Daniel Webster Scholars Program. Oregon’s Supreme Court has approved a similar path in principle, and a committee is fleshing out details. These pathways assure that future lawyers learn all of the knowledge and skills they need to protect clients; they also keep the final licensing decision in the hands of bar examiners, rather than law school professors.

How do these programs work? How do they achieve reliability and fairness in a feasible manner? I’ll address those issues in future posts. But for an overview, see this research guide that I coauthored with Logan Cornett.

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, Legal Education No Comments YetPublic Comment on the Bar Exam

David Lat is hosting a “Notice and Comment on the Bar Exam” at Original Jurisdiction. Several commentators have offered thoughtful insights. Here’s mine:

One of the many problems with the bar exam is that it doesn’t test the knowledge and skills that new lawyers really need. The exam was designed based on “gut instincts” about that knowledge and skills but, as often is the case, gut instincts were wrong. The problem was compounded by well intentioned efforts to create a national exam, which has resulted in candidates memorizing a vast number of federal or “consensus” rules that they will never use in practice.

But now we have good evidence about the knowledge and skills that new lawyers actually use. NCBE’s recent practice analysis offers some insights, and the Building a Better Bar study (which I coauthored with Logan Cornett) offers more. NCBE is now building a better exam around those studies, but a written exam can’t capture many of the skills that are essential to lawyering–and it’s hard to capture the type of knowledge most new lawyers use in a uniform national exam.

States like Oregon, California, Minnesota, and Utah are considering much better alternatives, with Oregon in the lead. It is possible to assess lawyering knowledge and skills through either law school coursework (including clinics and other experiential work) or post-graduate supervised practice. For both of these pathways, bar examiners would make the final decision based on portfolios of work product and assessments from professors or others. And it is feasible to construct both of these pathways with sufficient reliability, fairness, and validity.

The benefits of change? Cheaper pathways to licensure for candidates, better protection of the public, and (most likely, given the stereotype threat that affects high stakes testing) a more diverse profession. What stands in the way? Outdated ideas about how lawyers think and work, legal education’s reluctance to embrace more experiential education, our profession’s reluctance to innovate, and good old fashioned protectionism (the bar exam may exclude more lawyers than these alternatives would).

It’s time to honor our avowed commitments to open the profession to all qualified candidates, protect the public, and increase diversity. The bar exam is not achieving those goals.

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, Legal Education No Comments YetThis Year Is Still Different: An Outdated Bar Exam in Troubled Times

** This post is coauthored with Sara J. Berman, Marsha Griggs, and Carol Chomsky. All four of us are members of the Collaboratory on Legal Education and Licensing for Practice, a group of 10 scholars who have studied and written about the bar exam, licensing, and legal education for many years.**

Applicants for the July 2022 bar exam are buckling down for their final days of bar study. After two years of delays, remote testing, and other COVID-related changes, states have returned to traditional bar examination practices. For most applicants, this means two days of testing in large convention centers or hotel ballrooms. Following tradition, applicants will again answer questions from memory about a dozen or more doctrinal areas.

But this year’s examinees are different from those who preceded them. The pandemic overshadowed the entire law school career of 2022 graduates. Classes abruptly went online during their first year. Many received only pass/fail grades for their spring semester. That was essential relief for an upended semester, but the remedy deprived students of more nuanced information about their progress.

The pandemic continued to dog the class of 2022, limiting both work and externship opportunities. Many lost the chance to meet mentors, work in law offices, and develop confidence in their lawyering abilities. Second-year classes remained mostly online, escalating zoom fatigue and isolation. Even during their third year, when restrictions eased, extra-curricular activities and meetings were limited. Peers and professors hurried out of the room after class, reluctant to expose themselves to the latest COVID variant. Informal exchanges about the law, lawyering, and career prospects were limited for this class of aspiring attorneys.

And that’s not all. The class of 2022 experienced George Floyd’s murder at the end of their first year, a bloody attack on democracy and the Capitol during their second year, and a leaked opinion reversing Roe v. Wade during their third year. Whatever their personal beliefs about abortion, the leaked Dobbs opinion raised alarming questions about the Constitution, constitutional interpretation, and the future of other rights guaranteed by previous Courts—just as these students started studying Constitutional Law for the bar exam.

And then there were continued police shootings of unarmed Black people, attacks on Asian American women, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, heartbreaking gun violence, and our ongoing failure to address planetary destruction. These are unsettling times for anyone committed to the rule of law. For law students still exploring their future as lawyers, the times weren’t just unsettling—they have been devastating. They may doubt both the rule of law and their own ability to affect the world around them.

Now these graduates must prepare for a difficult exam that they know bears little relationship to their practice as fledgling lawyers. Research by NCBE and others has confirmed this mismatch. A new exam may address some of these flaws, but that exam won’t be ready until 2026. Meanwhile, today’s graduates must recall hundreds of detailed rules from memory. They must also prepare to answer essay questions on conflicts of law, family law, secured transactions, and trusts and estates—all subjects that NCBE has decided need not be tested. And they will not have a chance to show their competence at negotiation, client counseling, and other skills that NCBE now acknowledges should be assessed.

As a profession, we have a responsibility to help today’s bar takers. Pandemic graduates carry a heavy load of mental distress. More than a third show symptoms of depression, and 11% have seriously considered suicide during the last year. Those burdens may impair their preparation for the bar exam and their performance on it. If they do, we can’t blame the graduates for the world that surrounds them. Nor can we blame the academic support faculty who are working double-time to help this group of graduates succeed.

No, we need to look to the profession and what we can all do to help. Several states are considering non-exam pathways to licensure. If an experiential education path had existed for current graduates, they might have built a strong sense of their lawyering efficacy during law school—while learning skills and reinforcing the doctrinal knowledge they will use in practice and. If supervised practice pathways existed, recent graduates could be demonstrating their knowledge and skills by assisting real clients and learning from supervisors this month, rather than by grinding through daily doses of multiple-choice practice questions.

We have confidence in this year’s bar applicants: confidence in their abilities, their grit, and their determination. But even in the best of times, less than three-quarters of graduates pass the bar exam on their first try. And the failure rates fall disproportionately on graduates of color, the same individuals who suffered greater physical and financial burdens from COVID; emotional stress from police killings and other manifestations of racism; and loss of important mentoring opportunities during their law school years.

This, we know, is not the best of times. Offer as much encouragement and support as you can to bar-takers this week. And get involved with activities in your state to reform our licensing system. Do it for both our graduates and the clients they will serve.

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, Law Schools, Law Students No Comments YetGrowth of the Law

How much has the body of legal rules grown over the last fifty years? Daniel Martin Katz, together with colleagues in the United States and Germany, offers some intriguing insights into that question. In a recent paper, Katz and colleagues estimate that the United States Code added about 322,600 new chapters, parts, or sections in just the 22 years stretching from 1998 to 2019. Those additions represent a 63% increase in the number of structural elements in the Code.

Growth in federal regulations was even more aggressive during that period. Chapters, parts, or sections of the Code of Federal Regulations increased from 1.4 million in 1998 to 2.7 million in 2019–an increase of 91%.

If federal law grew this much between 1998 and 2019, how much did it grow in the decades before 1998? It is unlikely that Congress and federal agencies were more active after 1998 than in the decades just before that time. And what about growth of statutes and regulations at the state and local level? Or the growth of legal rules generated by judicial decisions? How much more “law” is there today than there was 50 years ago?

I offer here a small complement to the research of Katz and others: a description of the growth in federal constitutional rules governing criminal procedure. At the end, I offer a few preliminary thoughts about why the substantial growth of legal rules matters.

Method

My method is embarrassingly humble compared to the sophisticated data analytics used by Katz and his colleagues. But measuring growth in the federal constitutional law of criminal procedure is much simpler than assessing growth in the United States Code or Code of Federal Regulations. Scholars need sophisticated methods to measure the latter growth; for my project, a much simpler method sufficed.

The language in the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution has not changed during the last 50 years, so growth in this field consists of judicial interpretations. I limited my study to decisions rendered by the Supreme Court of the United States, which (in these fields) bind all state and federal actors. Decisions by lower courts may signal changes in the law, but those changes do not become nationally binding until accepted by the High Court.

Conversely, I considered every SCOTUS decision as a change of some magnitude in the law. The Supreme Court does not accept cases that merely apply existing law to new facts. Instead, the Court grants certiorari only in cases that raise a new legal issue and/or represent a conflict among the lower courts. I decided, therefore, to count SCOTUS decisions explicating the constitutional law of criminal procedure through 1971–and then to contrast that number with the number of decisions in the same field rendered in 1972 or later.

As a source, I used a recent outline of the federal constitutional law of criminal procedure, Criminal Procedure, by Paul Marcus and Melanie D. Wilson (20th ed. 2021). I chose that text because it offers a concise, yet complete, overview of the field; includes significant historical discussion; and uses a format that made counting SCOTUS decisions relatively easy.

My method, like most estimates, is imprecise. Marcus and Wilson might have omitted some key decisions from their outline–although based on my knowledge of the field, the outline is quite complete. Some older decisions may have been superseded by more recent citations, which would lead to undercounting of decisions from before 1972. Marcus and Wilson’s frequent discussion of historical context, however, helped guard against this. Some decisions, finally, may have been double counted if they appeared in more than one discussion. One reason I chose the Marcus and Wilson text, however, was their diligent use of “supra” to cite cases that had been discussed previously. Overall, the estimates below offer a reasonable picture of how the federal constitutional law of criminal procedure has expanded during the last 50 years.

Results

I counted 160 pre-1972 SCOTUS decisions on the federal constitutional law of criminal procedure, and 692 of those decisions from 1972 through 2021. That represents an enormous expansion of the constitutional rules in this field: More than 430%. And, since most of the pre-1972 rules still bind the courts, the corpus of Supreme Court law in this field has grown from about 160 decisions to about 852 decisions. Lawyers studying or practicing criminal law today must master more than five times as many constitutional rules and nuances as their forebears did in 1971.

How did this growth come about? Some contemporary fields of constitutional jurisprudence emerged only after 1971. The Supreme Court, for example, first held a death penalty statute unconstitutional in Furman v. Georgia (1972). The Court’s increasingly detailed exposition of when and how the death penalty may be imposed all occurred after that year.

Similarly, much of the constitutional law governing collateral attacks on criminal convictions developed after 1971. The Warren Court suggested a broad role for these attacks in Fay v. Noia (1963), but subsequent Courts have cut back on the use of habeas corpus through dozens of decisions creating a complex set of rules limiting these challenges.

Explosive growth, however, has occurred even in fields that were well established by 1971. By that year, the Supreme Court had laid the foundation for the modern law of search and seizure, holding that the Fourth Amendment protects reasonable expectations of privacy (Katz v. United States 1967); that an arrest must be based on probable cause (Beck v. Ohio 1964); that the protections provided by the Fourth Amendment bind the states (Wolf v. Colorado 1949); and that the exclusionary rule likewise applies to the states (Mapp v. Ohio 1961). The Court had also recognized the various exceptions to the warrant requirement that it still permits today. In all, Marcus and Wilson cite 36 decisions delimiting the constitutional law of search and seizure through the end of 1971.

Since that time, however, the Court has added at least 198 new opinions–an increase of 550%. Those opinions have generated an extraordinarily detailed law of the Fourth Amendment. Before 1972, for example, the Court had done little to specify what expectations of privacy are reasonable enough to elicit Fourth Amendment protection. Now we know that individuals lack a reasonable expectation of privacy in their handwriting (United States v. Mara 1973); the sound of their voices (United States v. Dionisio 1973); telephone numbers they dial (Smith v. Maryland 1979); their bank records (Fisher v. United States 1976); the color and composition of the paint on their cars (Cardwell v. Lewis 1974); odors that a dog can detect from their luggage (United States v. Place 1983) or automobiles (Illinois v. Cabales 2005); the contents of their privately owned fields (Oliver v. United States 1984) and barns (United States v. Dunn 1987); objects on their private property that are visible from a low-flying helicopter (Florida v. Riley 1989) or through high-powered cameras (Dow Chemical Co. v. United States 1986); and any garbage they leave by the curb (California v. Greenwood 1988). The Court has approved warrantless searches in these and other areas.

On the other hand, the Court has recognized a reasonable expectation of privacy (or other Fourth Amendment protection) for the feel of an individual’s luggage (Bond. v. United States 2014); the movement of a car on public highways when tracked by a GPS tracking device (United States v. Jones 2012); the location of a cell phone (Carpenter v. United States 2018); odors a dog might detect from the front porch of a home (Florida v. Jardines 2013); the heat emitted from a home when detected by a thermal imager (Kyllo v. United States 2001); and data stored on a cell phone (Riley v. California 2014).

These post-1971 decisions do not represent obvious applications of Katz and other existing Fourth Amendment principles. Indeed, many of these opinions were issued by a divided Court. Instead, these and other decisions represent a detailed codification of the Fourth Amendment, with specific rules that criminal law practitioners must know or be able to find.

Similar growth has occurred in other areas of constitutional criminal procedure, including the legal principles governing the Sixth Amendment right to counsel; the contours of the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination; and the prosecution’s obligation to disclose information to the defense. The constitutional law of criminal procedure is much more complex today than it was fifty years ago.

Implications

Why does growth in the law matter, whether with repect to the constitutional rules of criminal procedure or in any other area? For the individuals and organizations seeking to comply with the law, growth may promote clarity. Police today know that they may not squeeze luggage to search for drugs, but may use a dog to sniff for that contraband. Similarly, homeowners know that the police may photograph their property from low-flying helicopters, but may not use thermal imaging devices to probe further.

On the other hand, this clarity increases complexity. Non-lawyers today have little hope of understanding the scope of their constitutional protections, and even lawyers struggle to keep up with all of the Court’s rulings. Criminal law practice has splintered into specialties, as lawyers strive to master these complex fields. A lawyer specializing in white-collar defense would have to bone up on the Fourth Amendment rules governing drunk driving cases to defend the latter type of case. And a lawyer who handles plea bargains and trials would have to master a new field before handling a collateral attack on a conviction.

As a law professor, I am particularly interested in how this growth in the law affects the ways in which we teach, learn, and test legal knowledge. In 1971, a professor of criminal procedure could lead students through all of the Supreme Court’s major opinions. The class could study those opinions in depth, studying the evolution of legal principles and their possible application to novel situations.

Today, we try to do the same, but there is so much more law to cover. How does one trace the evolution of principles through so many cases? And, although there are always novel situations to discuss, there is so much law to learn as a predicate for those discussions.

Equally important, our traditional ways of teaching omit some of the most valuable tools we can impart to today’s students. No one can remember the details of a criminal procedure class for very long, so how do practicing attorneys organize, remember, access, or find that information? Doctrinal professors have started teaching students about reference books and research tools in their field, but we need to do more of that. Similarly, we should help students develop the type of “cheat sheets” that practicing lawyers use to remember key points and assess cases. Today, those intellectual skills are as important as case analysis and synthesis.

And what about testing? Should exams require students to remember fine details? Or to discuss fundamental principles? Should exams be open or closed book? Most of my law school exams were open book during the 1970’s, a practice that seems even more appropriate today given the growth of the law since that time. Yet the trend in law school exams seems to have moved in the opposite direction.

How, finally, has growth of law affected the bar exam? The Multistate Bar Exam debuted in February of 1972, almost exactly 50 years ago. At that time, the criminal procedure portion of the exam would have been limited to testing the fundamental principles outlined in 162 or so Supreme Court opinions. That’s a healthy swath of law, especially for a closed book test covering numerous other subjects, but the field today is more than five times larger.

Does lawyering competence require memorizing the detailed rules that characterize much of the law today? That is both impractical and counterproductive. Today’s lawyers, more than ever before, need to know how to find rules–not recall them. Our contemporary definition of lawyering competence should focus on knowledge of threshold concepts (much like the foundational principles that existed in 1971) and the skills needed to implement those concepts and serve clients.

NCBE is designing a “Next Generation” of the bar exam that it suggests will test doctrinal rules “less broadly and deeply within the subjects covered.” At the same time, the new exam will place “greater emphasis . . . on assessment of lawyering skills.” If implemented, those commitments will serve our profession well: They recognize the enormous growth of legal rules over the last fifty years, as well as the importance of lawyering skills in managing that growth and serving clients effectively.

Uncategorized, Bar Exam, Criminal Law, Legal Education, SCOTUS No Comments YetA Better Bar Exam—Look to Upper Canada?

Today, tens of thousands of aspiring lawyers across the United States sit for the bar exam in a ritual that should be designed to identify who has the ability to be a competent new lawyer. Yet a growing chorus of critics questions whether the current knowledge-focused exam is the best way to draw that line and protect the public. As Professor Deborah Merritt has noted, “On the one hand, the exam forces applicants to memorize hundreds of black-letter rules that they will never use in practice. On the other hand, the exam licenses lawyers who don’t know how to interview a client, compose an engagement letter, or negotiate with an adversary.”

For years, the response to critiques of the bar exam has been, in effect: “It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we can do if we want a psychometrically defensible exam.” The Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC), which governs the law licensing process for the province of Ontario, developed a licensing exam that calls that defense into question.

Overview of Law Society of Upper Canada Licensing Exam

The LSUC uses a 7-hour multiple-choice test consisting of 220 to 240 multiple-choice questions to test a wide range of competencies. For barristers (the litigating branch of the profession), that includes ethical and professional responsibilities; knowledge of the law; establishing and maintaining the lawyer-client relationship; problem/issue Identification, analysis, and assessment; alternative dispute resolution; litigation process; and practice management issues. A 2004 report explains how the LSUC identified key competencies and developed a licensing test based upon them.

Unlike the US exams, the LSUC exam is open-book, so it tests the ability to find and process relevant information rather than the ability to memorize rules. Most important, it tests a wider range of lawyering competencies than US exams, and it does so in the context of how lawyers address real client problems rather than as abstract analytical problems.

Below, we discuss how these differences address many of the critiques of the current US bar exams and make the LSUC exam an effective test of new lawyer competence. We also provide sample questions from both the LSUC and the US exam.

Open-Book Exam

Like all bar licensing exams in the United States (with the New Hampshire Daniel Webster Scholars Program as the sole exception), the LSUC exam is a pencil-and-paper timed exam. However, unlike any United States exam, including the Uniform Bar Exam, the LSUC licensing exam is open book.

The LSUC gives all candidates online access to materials that address all competencies the exam tests and encourages candidates to bring those materials to the exam. To help them navigate the materials, candidates are urged to create and bring to the exam tabbing or color-coding systems, short summaries of selected topics, index cards, and other study aids.

Lawyering is an open-book profession. Indeed, it might be considered malpractice to answer a legal problem without checking sources! As we have previously noted, good lawyers “…know enough to ask the right questions, figure out how to approach the problem and research the law, or know enough to recognize that the question is outside of their expertise and should be referred to a lawyer more well-versed in that area of law.” Actually referring a problem to someone else isn’t a feasible choice in the context of the bar exam, of course, but accessing the relevant knowledge base is.

The open-book LSUC exam tests a key lawyering competency untested by the US exam—the ability to find the appropriate legal information—and it addresses a significant critique of the current U.S. exams: that they test memorization of legal rules, a skill unrelated to actual law practice.

Candidates for the bar in Canada no doubt pore over the written material to learn the specifics, just as US students do, but they are also able to rely on that material to remind them of the rules as they answer the questions, just as a lawyer would do.

Testing More Lawyering Competencies

Like all bar exams in the US, the LSUC exam assesses legal knowledge and analytical skills. However, unlike US bar exams, the LSUC exam also assesses competencies that relate to fundamental lawyering skills beyond the ability to analyze legal doctrine.

As Professor Merritt has noted, studies conducted by the National Conference of Bar Examiners [NCBE] and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System confirm the gaps between the competencies new lawyers need and what the current US bar exams test, citing the absence of essential lawyering competencies such as interviewing principles; client communication; information gathering; case analysis and planning; alternative dispute resolution; negotiation; the litigation process; and practice management issues.

The NCBE has justified their absence by maintaining that such skills cannot be tested via multiple-choice questions. However, as illustrated below, the LSUC exam does just that, while also raising professional responsibility questions as part of the fact patterns testing those competencies.

Testing Competencies in Context of How Lawyers Use Information

The LSUC exam attempts to capture the daily work of lawyers. Rather than test knowledge of pure doctrine to predict a result as the US exams tend to do, the LSUC used Bloom’s taxonomy to develop questions that ask how knowledge of the law informs the proper representation of the client.

The LSUC questions seek information such as: what a client needs to know; how a lawyer would respond to a tribunal if asked “x”; where a lawyer would look to find the relevant information to determine the steps to be taken; and what issues a lawyer should research. That testing methodology replicates how lawyers use the law in practice much more effectively than do the US exams.

The LSUC exam format and content addresses a significant critique of US bar exams—that those exams ask questions that are unrelated to how lawyers use legal doctrine in practice and that the US exams fail to assess many of the key skills lawyers need.

Sample Questions from the LSUC and the MBE

Here is a sampling of LSUC questions that test for lawyering skills in a manner not addressed in US exams. These and other sample questions are available on the Law Society of Upper Canada’s website:

- Gertrude has come to Roberta, a lawyer, to draw up a power of attorney for personal care. Gertrude will be undergoing major surgery and wants to ensure that her wishes are fulfilled should anything go wrong. Gertrude’s husband is quite elderly and not in good health, so she may want her two adult daughters to be the attorneys. The religion of one of her daughters requires adherents to protect human life at all costs. Gertrude’s other daughter is struggling financially. What further information should Roberta obtain from Gertrude?

(b) The state of Gertrude’s marriage.

(c) Gertrude’s personal care wishes.

(d) Gertrude’s health status.

- Tracy was charged with Assault Causing Bodily Harm. She has instructed her lawyer, Kurt, to get her the fastest jury trial date possible. The Crown has not requested a preliminary inquiry. Kurt does not believe that a preliminary inquiry is necessary because of the quality of the disclosure. How can Kurt get Tracy the fastest trial date?

(b) Bring an 11(b) Application to force a quick jury trial date.

(c) Conduct the preliminary inquiry quickly and set down the jury trial.

(d) Elect on Tracy’s behalf trial by a Provincial Court Judge.

- Peyton, a real estate lawyer, is acting for a married couple, Lara and Chris, on the purchase of their first home. Lara’s mother will be lending the couple some money and would like to register a mortgage on title. Lara and Chris have asked Peyton to prepare and register the mortgage documentation. They are agreeable to Peyton acting for the three of them. Chris’ brother is also lending them money but Lara and Chris have asked Peyton not to tell Lara’s mother this fact. Should Peyton act?

(b) No, because there is a conflict of interest.

(c) Yes, because the parties are related.

(d) No, because she should not act on both the purchase and the mortgage.

- Prior to the real estate closing, in which jurisdiction should the purchaser’s lawyer search executions?

(b) Where the seller’s real property is located.

(c) Where the seller’s personal property is located.

(d) Where the seller is moving.

[These questions test the applicant’s understanding of: the information a lawyer needs from the client or other sources, strategic and effective use of trial process, ethical responsibilities, and knowledge of the real property registration system, all in the service of proper representation of a client. Correct answers: c, a, b, b.]

Compare these questions to typical MBE questions, which focus on applying memorized elements of legal rules to arrive at a conclusion about which party likely prevails. [More available here.]

- A woman borrowed $800,000 from a bank and gave the bank a note for that amount secured by a mortgage on her farm. Several years later, at a time when the woman still owed the bank $750,000 on the mortgage loan, she sold the farm to a man for $900,000. The man paid the woman $150,000 in cash and specifically assumed the mortgage note. The bank received notice of this transaction and elected not to exercise the optional due-on-sale clause in the mortgage. Without informing the man, the bank later released the woman from any further personal liability on the note. After he had owned the farm for a number of years, the man defaulted on the loan. The bank properly accelerated the loan, and the farm was eventually sold at a foreclosure sale for $500,000. Because there was still $600,000 owing on the note, the bank sued the man for the $100,000 deficiency. Is the man liable to the bank for the deficiency?

(b) No, because the bank’s release of the woman from personal liability also released the man.

(c) Yes, because the bank’s release of the woman constituted a clogging of the equity of redemption.

(d) Yes, because the man’s personal liability on the note was not affected by the bank’s release of the woman.

- A man arranged to have custom-made wooden shutters installed on the windows of his home. The contractor who installed the shutters did so by drilling screws and brackets into the exterior window frames and the shutters. The man later agreed to sell the home to a buyer. The sales agreement did not mention the shutters, the buyer did not inquire about them, and the buyer did not conduct a walkthrough inspection of the home before the closing. The man conveyed the home to the buyer by warranty deed. After the sale closed, the buyer noticed that the shutters and brackets had been removed from the home and that the window frames had been repaired and repainted. The buyer demanded that the man return the shutters and pay the cost of reinstallation, claiming that the shutters had been conveyed to him with the sale of the home. When the man refused, the buyer sued. Is the buyer likely to prevail?

(b) No, because the window frames had been repaired and repainted after removal of the shutters.

(c) Yes, because the shutters had become fixtures.

(d) Yes, because the man gave the buyer a warranty deed and the absence of the shutters violated a covenant of the deed

[Correct answers: d, c]

We Can Build a Better Bar Exam

As illustrated above, the LSUC exam shows that it is possible to test a far wider range of competencies than those tested in US bar exams.

Does the LSUC exam address all of the flaws of US bar exams? No—one problem that persists for both the LSUC and US exams is the requirement for rapid answers (less than 2 minutes per question), which rewards an ability and practice not associated with effective lawyering.

Does the LSUC exam fully address experiential skills? No—LSUC also requires applicants to “article” (a kind of apprenticeship with a law firm) or participate in the Law Practice Program (a four-month training course and a four-month work placement).

But the exam does what the NCBE has told us cannot be done. It is a psychometrically valid exam that assesses skills far beyond the competencies tested on US bar exams: skills such as interviewing, negotiating, counseling, fact investigation, and client-centered advocacy. And its emphasis is on lawyering competencies—using doctrine in the context of client problems.

Eileen Kaufman is Professor of Law at the Touro College, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center.

Andi Curcio is Professor of Law at the Georgia State University College of Law.

Carol Chomsky is Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School.

Higher Education, Bar Admissions, Bar Exam, Canada, LSUC, NCBE, The Law Society of Upper Canada, Uniform Bar Exam No Comments YetThe High Cost of Not Lowering the Bar

Gilbert A. Holmes is Dean and Professor of Law at the University of La Verne College of Law

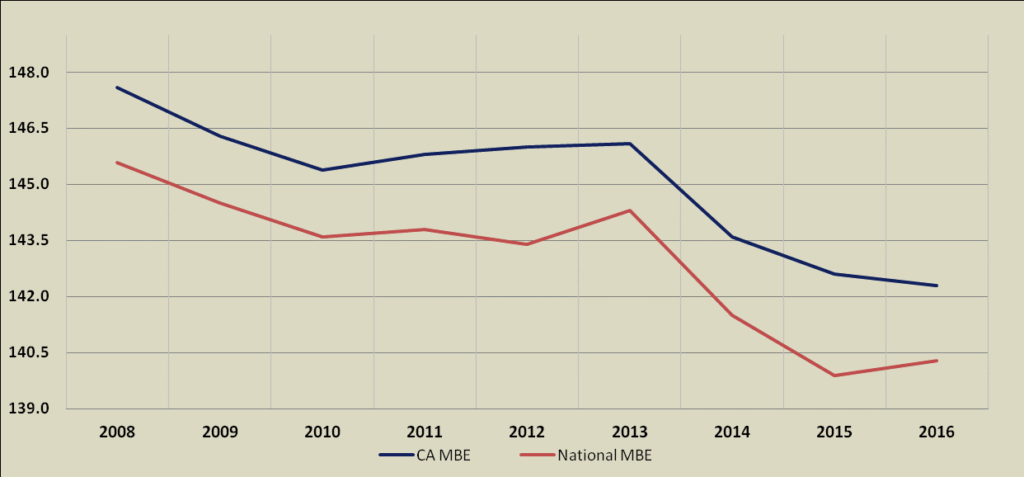

In July of 2016, graduates from ABA-approved law schools in California had a first-time General Bar Examination pass rate of 62 percent, and all bar takers in the state had a first-time pass rate of 56 percent. These numbers are down from previous years, sparking debate, discussion and deliberation about the reason for the decline and what can be done about it.

Deans of ABA-approved law schools in California have been calling for a lowering of the cut score that serves as the basis for grading of the exam. California has the second highest cut score in the country. It also has the lowest pass rate, even though researcher Roger Bolus reported to the State Bar of California that the state’s bar exam takers perform higher than the national average on the only portion of the exam that every state except Louisiana administers—the MBE.

The State Bar has responded to this call by engaging in a number of studies about the content and validity of the bar exam and the California grading system. (more…)

» Read the full text for The High Cost of Not Lowering the Bar

Data, Rules, Bar Exam, California State Bar No Comments YetBar Exam Scores and Lawyer Discipline

Robert Anderson and Derek Muller have posted a provocative paper, The High Cost of Lowering the Bar, in which they argue that “bar exam score is significantly related to likelihood of State Bar discipline throughout a lawyer’s career.” Thus, they warn, “lowering the bar examination passing score,” as several California law deans have advocated, “will likely increase the amount of malpractice, misconduct, and discipline among California lawyers.”

Anderson and Muller urge the state bar to collect more detailed data on the relationship between bar scores and lawyer discipline–and then to consider the possible impact on attorney misconduct if the Supreme Court lowers the passing score. “The data we have collected,” they conclude, “should raise serious concerns about the effect on consumers of lowering the passing score.”

What type of correlation did Anderson and Muller identify? Should it affect decisions about the passing score for the bar exam? Let’s take a closer look.

» Read the full text for Bar Exam Scores and Lawyer Discipline

Data, Bar Exam, Discipline View Comments (5)More on the Bar Exam: Correlation and Competence

Derek Muller has identified an intriguing study of alternative ways to assess bar applicants. In 1980, the California bar examiners worked with a research team to explore the desirability of testing a wider range of lawyering skills on the bar exam. The researchers designed a two-day supplement to the bar exam and invited all July test-takers to participate in the supplemental exercise. More than 4,000 test-takers volunteered and, using appropriate sampling methods, the researchers chose 500 to participate. A few volunteers were unable to complete the exercise due to illness, so the final sample included 485 bar examinees.

These examinees completed the supplemental exercises in August 1980, shortly after taking the regular July exam. For two days, the examinees interviewed clients, drafted discovery plans, prepared letters, wrote trial briefs, cross-examined witnesses, and made arguments to mock juries. Each day’s work involved 5-6 tasks focused on a single client matter. Professional actors played the role of clients, and the researchers developed elaborate protocols for scoring the exercises.

How did results on the supplemental exam compare to those on the conventional test?

» Read the full text for More on the Bar Exam: Correlation and Competence

Data, Student Body, Bar Exam No Comments YetReflections of a Bar Exam Skeptic

Robert Anderson has posted a thoughtful comment on the bar exam in which he dubs me a “bar exam skeptic.” I accept the label with pride: I have been deeply skeptical of the bar exam for years. I first wrote about the exam in 2001, when the national pass rate for first-time takers was a relatively high 77% (see p. 23). My skepticism today, with a national pass rate of 69%, is no greater or smaller. As I wrote recently, it’s time to convene a National Task Force to examine our bar admissions process.

Who Cares About the Bar Exam?

As Professor Anderson rightly observes, decanal concerns about the bar exam have risen as pass rates have fallen. That’s human nature. The content and scoring of the bar exam are boring subjects for alumni gatherings, graduation speeches, or law review submissions. Few legal educators spontaneously write about setting cut scores, scaling essay questions, or equating test scores over time. The bar exam is like plumbing: most people take it for granted until something goes wrong.

But now the bar exam pipes are leaking and people are paying attention. The leak doesn’t mean we should patch things up just to revive pass rates; the bar exam should measure competence, not admit a predetermined number of lawyers. But now that people are paying attention, this is a good time to consider whether we’re using the right type of filter and piping in our rather antiquated system.

» Read the full text for Reflections of a Bar Exam Skeptic

Student Costs, Teaching, Bar Exam No Comments YetOur Broken Bar Exam

The bar exam is broken: it tests too much and too little. On the one hand, the exam forces applicants to memorize hundreds of black-letter rules that they will never use in practice. On the other hand, the exam licenses lawyers who don’t know how to interview a client, compose an engagement letter, or negotiate with an adversary.

This flawed exam puts clients at risk. It also subjects applicants to an expensive, stressful process that does little to improve their professional competence. The mismatch between the exam and practice, finally, raises troubling questions about the exam’s disproportionate racial impact. How can we defend a racial disparity if our exam does not properly track the knowledge, skills, and judgment that new lawyers use in practice?

We can’t. In the language of psychometricians, our bar exam lacks “validity.” We haven’t shown that the exam measures the quality (minimal competence to practice law) that we want to measure. On the contrary, growing evidence suggests that our exam is invalid: the knowledge and skills tested by the exam vary too greatly from the ones clients require from their lawyers.

We cannot ignore the bar exam’s invalidity any longer. Every legal educator should care about this issue, no matter how many of her students pass or fail the exam. The bar exam defines the baseline of our profession. If the exam tests the wrong things, we have a professional obligation to change it.

* * *

For the rest of this essay, please see aalsnews. I discuss the concept of exam validity, our lack of agreement on “minimal competence,” and how educators and practitioners could work together to solve these serious problems.

Rules, Bar Exam View Comments (3)About Law School Cafe

Cafe Manager & Co-Moderator

Deborah J. Merritt

Cafe Designer & Co-Moderator

Kyle McEntee

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Around the Cafe

Subscribe

Categories

Recent Comments

- Law School Cafe on Scholarship Advice

- COVID Should Prompt Us To Get Rid Of New York’s Bar Exam Forever - The Lawyers Post on ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

- Targeted Legal Staffing Soluti on COVID-19 and the Bar Exam

- Advocates Denver on Women Law Students: Still Not Equal

- Douglas A. Berman on Ranking Academic Impact

Recent Posts

- The Bot Takes a Bow

- Fundamental Legal Concepts and Principles

- Lay Down the Law

- The Bot Updates the Bar Exam

- GPT-4 Beats the Bar Exam

Monthly Archives

Participate

Have something you think our audience would like to hear about? Interested in writing one or more guest posts? Send an email to the cafe manager at merritt52@gmail.com. We are interested in publishing posts from practitioners, students, faculty, and industry professionals.