Kudos to California

In February 2012, the California Bar Association appointed a task force to “examine whether the State Bar should develop a regulatory requirement for a pre-admission competency training program.” The group, dubbed the “Task Force on Admissions Regulatory Reform” (TFARR), oversaw hearings, deliberations, and consultations with key constituencies. It issued an initial report in 2013, which was adopted by the bar association’s board of trustees, then held a second round of hearings and deliberations to refine the recommendations for implementation.

That second report has been approved by the bar and awaits action by the California Supreme Court. What’s noteworthy about all of this? If approved, law graduates seeking to join the California bar will have to meet three new requirements. Law schools around the country will also have to help their California-bound students satisfy the first requirement: demonstrating completion of “15 units of practice-based, experiential coursework.”

I see both positives and negatives in the California proposal but, on balance, it’s a strong step forward. The proposal is a lengthy one, so I will explore it in several posts. To start, here are the features I find most appealing:

Process

The TFARR reports suggest a very thoughtful process. Academics and practitioners seem to have spent a lot of time talking with one another, as well as pondering what would be best for clients. The final report carefully considers objections from various stakeholders (especially law schools) and responds to them. I think we should listen to what the California task force has to say, not just because the state is big and diverse, but because intelligent people devoted a lot of attention to this proposal.

Practice-Based Experiential Coursework

For academics, the most controversial part of the California proposal is its requirement that students complete “15 units of practice-based experiential coursework . . . designed to foster the development of professional competencies.” The requirement is more demanding than the ABA’s recent mandate that students complete 6 hours of “experiential” courses; this difference has drawn strong opposition from some law school deans.

But let’s look more closely at the terms of the California proposal. Students can fulfill 6 of the 15 units through work with outside employers–including paid positions with private firms. This is an innovative idea that I explore further below.

California also allows students to count fractional parts of an academic course, as long as the course offers at least a half credit of the “practice-based experiential coursework” described in the requirements. In my 4-credit Evidence course, for example, I could devote one-eighth of the semester to an exercise (or a set of 2-3 exercises) that would allow my students to explore evidentiary principles in the context of motion writing, fact gathering, negotiation, ethical quandaries, or other professional work. I know professors who already do this, with appropriate feedback and reflection; it’s a great way to teach evidence. Courses structured like this would generate 1/2 credit toward the California requirement.

The California Task Force, furthermore, does an excellent job of defining the educational experiences that develop professional expertise. Too many professors still assume that “practice-based” courses consist solely of finding the courthouse, filing some papers, and listening to war stories from adjuncts.

As the California report suggests, those images are far from the truth. First-rate professional education draws from decades of cognitive science work illuminating the ways in which professionals develop expertise. That science, like the TFARR report, recognizes that there are four keys to cultivating expertise: teach the conceptual underpinnings, give students an opportunity to apply concepts in novel settings, provide feedback, and encourage student reflection.

Those parameters describe first-rate teaching, and it is especially appropriate to use those techniques to teach the competencies described in the California report. As knowledge of legal doctrine spreads rapidly through the population, lawyers’ professional expertise depends increasingly on their ability to apply that doctrine in the context of expert interviewing, counseling, cost-benefit analysis, and project management. Those skills are not trivial add-ons; they are complex cognitive activities that lawyers need to know and integrate with their knowledge of legal doctrine.

Is 15 Hours Too Much?

A prominent group of deans has objected to the California proposal partly on the ground that a 15-hour requirement is too much, too soon. But from a client’s, employer’s, or student’s perspective, it’s hard to believe that 15 hours of practice-based education is too much.

First, we’re talking about high-quality educational experiences, ones that provide both conceptual development and feedback. Courses that satisfy the California requirements will embody top-of-the-line pedagogy. Second, these educational opportunities will occur in just the areas where clients and employers find lawyers deficient.

Finally, and perhaps most important, these are the areas in which lawyers have the most potential to demonstrate their value. Clients can find legal doctrine on the web, through courthouse self-help materials, and through online services like Just Answer. Businesses increasingly have turned to compliance officers, human resource specialists, and other non-lawyers for help with legal doctrine. The potential advantage that lawyers hold over these competitors is the ability to integrate legal doctrine with lawyering-specific skills like interviewing, counseling, problem solving, and project management.

Lawyers have a special way of doing all of those things; we don’t interview like cops or counsel like social workers. But we need to teach students those ways, explore the concepts that undergird them, and help students practice. No one is born “interviewing like a lawyer.”

If we don’t give students a foundation in more of the skills that are special to our profession, we will hamper their ability to succeed in a competitive market. Knowledge of legal doctrine used to be lawyers’ competitive advantage; now it is the combination of that knowledge with other lawyer-specific skills.

Will these 15 hours diminish the amount of legal doctrine that law students learn? To some extent, but not nearly to the extent that critics seem to fear. Many professors already use practice exercises to teach advanced areas of legal doctrine; sophisticated concepts are hard to grasp without that contextual application. To the extent we lose some doctrinal principles along the way, that’s consistent with the traditions of legal education: we aim to teach fundamental cognitive processes that students can apply throughout their professional careers.

Clerkships and Apprenticeships

One of the most intriguing aspects of the California proposal is its creation of clerkships or “apprenticeships” that can fulfill up to 6 units of the practice-based education requirement. The rules for these experiences are different than those imposed by the ABA for credit-bearing externships. Most notable, students can be paid for these experiences. Summer and school-year jobs, in other words, can count. To do so, the employer must provide “an orientation session, active supervision, a system for assignments, timely oral and written feedback, a diversity of tasks and an opportunity for reflection.”

Once again, TFARR hits the nail on the head in terms of developing professional expertise. These requirements are just the ones that cognitive scientists have identified as essential for developing professional competency. If employers and schools take these requirements seriously, students will have much more educationally enriching workplace experiences. Many jobs already contribute to students’ education, but ones that follow these rules will add considerably more value.

Will law schools and employers take these requirements seriously? As professionals, we will be bound to do so; as educators, we should be eager to improve the quality of our students’ workplace experiences. On the employer side, I think that employers will discover a self interest in following these rules. These rules offer a template for educating new lawyers, one that many employers lack. If employers follow the California principles, I think they will realize enhanced productivity from their law students–as well as greater value from the graduates they hire more permanently.

At the very least, this is an experiment well worth trying. The California apprenticeship model lays the foundation for new types of collaboration between law schools and employers. That’s an outcome that could benefit schools, students, employers, and clients in myriad ways.

Clients

Let’s finish with clients, who are the focus of our professional obligations. Why does the California proposal help clients?

Lawyering is incredibly hard. It requires a wide range of knowledge, many interpersonal skills, and an ability to juggle very different inputs while problem solving (What does the client say she wants? What does she really want? What will the law allow? Could I change that law if I challenged it? Is the key fact I’m assuming true, or did that witness lie? How much time will my employer let me spend on all of this?)

The outcomes of this difficult task seriously affect other people’s lives. People go to prison, they lose custody of their children, they forfeit their businesses and homes. Or, sometimes, they prove their innocence, expose a civil rights violation, buy a dream home, or create a business that benefits an entire region.

Given the importance of our work to clients, combined with the difficulty of our tasks, we can never be complacent about legal education. We joke about how slowly law schools change, but it’s no joke. Schools have made many laudable changes during the last 35 years, but we were playing catch-up on many of them.

Every year, we ask our first-year students to stretch their minds and work harder than they’ve ever worked before. We need to do the same. Will we have to stretch ourselves to provide the opportunities required by the California proposal? Maybe, but it’s time for that stretch.

Like our students, we can learn to think in new ways and we can push ourselves to achieve more–so that they and their clients can achieve more. Let’s just do it.

Thin Skins

Appellate judges sometimes complain about the “negative bias” in law review articles. “Scholars don’t write about what we do right,” the judges grumble. “They only write when they think we’ve gotten something wrong.”

I can think of exceptions to this tendency, but I think the judges are largely right. There’s not much point to an article that praises a judicial opinion; the opinion speaks for itself. Colleagues and tenure reviewers, moreover, won’t be very impressed by an article that simply extols a court’s reasoning; we want evidence of the professor’s critical thinking. At the very least, that means the scholar should suggest an alternative ground for the court’s decision. Academic scholarship slants toward the critical.

The same is true when the media cover legal education, but law professors don’t like it one bit. In faculty lounges and blogs across the country, professors complain about the media’s bias against legal education. The press occasionally carries a story that paints law school in a positive light, but most of the stories are critical. When it comes to criticism, legal educators seem much better at giving than receiving.

Is This Different?

Is there a difference between the negative bias in legal scholarship and the critical slant in media reports about legal education? Some professors suggest that the media have a venal motive for their negative stories: criticism sells. That motive, however, is not so different from the one that motivates us as scholars to criticize more often than we praise. Our payments are tenure, promotion, respect–and the increased salaries that flow from those reputational enhancements. Even if we care more about reputations than dollars, we have personal motives that push us towards criticism.

Other professors might distinguish our academic critiques from media “hatchet jobs” by pointing to the conflicting policies that surround important judicial decisions. Resolutions that balance competing interests are inherently debatable; scholars perform a worthwhile public task when they examine the downsides of a court’s balance.

Legal education, however, also balances competing priorities. We weigh the time devoted to scholarship and teaching. We decide how much to invest in clinics and how much to allocate to seminars. We make curricular and cultural choices that signal the relative importance of serving business clients and individual ones. We determine whether to give scholarship dollars to students with high LSAT scores or to those with few financial resources.

These decisions affect the public interest: They shape the type of lawyers we graduate, the clients they choose to serve, and the skills they bring to that service. We may think we’ve struck all the right balances, but the public may not agree. The policy choices we make are as debatable as those that courts adopt.

“But,” some of my media-irritated colleagues complain, “the media don’t know anything about legal education. They write–and criticize us–out of ignorance. When we write about judicial opinions, we draw upon our extensive knowledge of the law.”

This is a fair distinction, but it points to the importance of media criticism rather than its unfairness.

The Duties of an Autonomous Profession

Law is an autonomous, self-regulated profession. We decide what counts as law practice, who gets to engage in that practice, and the type of education those practitioners receive. The public has almost no role in deliberating or deciding these matters.

The legal profession’s autonomy is particularly strong, because courts determine most of the rules that govern us. Judges are lawyers; most of them come from law practice, and many (especially in states with electoral systems) return to practice. Doctors must submit to regulation by judges and legislators, both groups that lack medical credentials. We submit primarily to regulation by our own kind.

Law schools benefit from two rings of autonomy. As educators, we vigorously defend our autonomy against the practicing bar. We claim superior knowledge of how to educate future lawyers, and we regularly assert that superiority in debates with the bar. Even when we succumb to pressure from practitioners, however, we still operate within the protected walls of the legal profession. Prospective clients and the public have very little say in what we do.

Members of the public have just two ways to affect the policy choices made by lawyers and law schools. One is through their purchasing power. If potential clients dislike the services provided by lawyers, or the prices charged by those lawyers, they can bargain for better/cheaper services, forego those services, or substitute services from unlicensed providers. Prospective law students, similarly, can negotiate for higher scholarships or pursue alternative careers if they don’t like the options offered by law schools.

All of this is happening in today’s market, but these consumer choices are a blunt instrument. Lawyers, after all, define the “practice of law” so we have the power to close down unlicensed providers. Law schools, meanwhile, offer the sole gateway to the profession in most states. These monopolies–over both services and education–limit the power of market signals. We may be feeling the market’s pinch in law practice and legal education, but the pinch would be stronger without our professional protections.

Equally important, market forces can’t tell us why prospective clients or law students are dissatisfied. Is it just a matter of price? Or do they want services/education in a different form?

To raise these issues, the public must turn to its second avenue for affecting policy choices in legal education and the profession: public criticism. Through blogs, mainstream media, and cocktail party conversations, the members of the public tell us their concerns about legal services and legal education.

Some of those concerns are misplaced; others suffer from ignorance. Most of us are guilty of the same faults when we criticize medical care, software design, or highway construction projects. Experts in every field put up with a lot of flak from lay consumers–who often compound their insults by acting as if they know more than the experts.

The flak, however, includes key insights–and it’s our duty as professionals to sort through the criticism for the points that matter. Experts know a lot, but they don’t know everything: Our very expertise can blind us to consumer needs and avenues of innovation. Self interest and professional pride can also make us resistant to calls for change. These dangers are particularly severe in a field–like law–where professionals regulate themselves.

Sociologists argue that professionals have a duty to accept public criticism with grace and thoughtfulness. That duty stems from our underlying societal bargain: We receive the power of self regulation in return for a promise to exercise that power in the public’s interest. We can’t fulfill our terms of the bargain if we’re not willing to listen to public criticism.

Responding to Criticism

I agree with the sociologists. As members of a self-regulating profession, we have a duty to listen carefully to public criticism. We don’t have to embrace every critique, and we certainly should correct misstatements. We should also explain why we do things the way we do, and we can invite the public to engage in dialogue with us.

But let’s stop whining about the criticism itself–just as most savvy judges have learned to hold their fire in the face of law review criticism. Public criticism is a sign that we matter. People care about the structure of the legal system, the accessibility of legal services, and the quality of the lawyers who serve them. We should care enough about what they think to listen courteously, clear up misunderstandings, and (every now and then) admit that they have a point.

Can We Close the Racial Grade Gap?

In response to last week’s post about the racial gap in law school grades, several professors sent me articles discussing ways to ameliorate this gap. Here are two articles that readers may find useful:

1. Sean Darling-Hammond (a Berkeley Law graduate) and Kristen Holmquist (Director of Berkeley’s Academic Support Program), Creating Wise Classrooms to Empower Diverse Law Students.

2. Edwin S. Fruehwald, How to Help Students from Disadvantaged Backgrounds Succeed in Law School.

Another excellent choice is Claude Steele‘s popular book, Whistling Vivaldi. Steele, who is currently Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost at UC Berkeley, is a leading psychology researcher. He originated the phrase “stereotype threat,” which explains a key cognitive mechanism behind the reduced performance of minority students in higher education. In his book, Steele offers highly accessible explanations of this mechanism.

Even better, the book describes some experimentally tested approaches for reducing stereotype threat and improving performance of minority students. The psychologists have not found a magic tonic, but they are pursuing some promising ideas.

How Hard Will It Be?

Many of the ideas offered by Steele, Darling-Hammond, Holmquist, and Fruehwald rest on principles of good teaching. We should, for example, teach all of our students how to read cases and analyze statutes, rather than let them flounder to learn on their own. The analytical skills of “thinking like a lawyer” can be taught and learned; they are not simply talents that arise mysteriously in some students.

Similarly, we should cover the basics in our courses, explaining the legal system rather than brushing over those introductory chapters as “something you can read if you need to review.” The latter approach is likely to increase stereotype threat, because it suggests “you don’t belong here and you’re behind already” to students who lack that information. Besides, you’d be surprised how many law students don’t understand the concept of a grand jury–even when they take my second-year Evidence course.

Positive feedback and formative assessment are also important tools; these techniques, like the ones described above, can benefit all students. They may be especially important for minority students, however, who are likely to suffer from both social capital deficits (i.e., lack of knowledge about how to study for law school exams) and culturally imposed self doubts. By giving students opportunities to try out their law school wings, and then offering constructive feedback, we can loosen some of the handicaps that restrain performance.

Harder Than That

These approaches, as well as others mentioned in the articles at the beginning of this post, are worth trying in the classroom. I think, though, that it will be much harder than most white professors imagine to remove the clouds of stereotype threat.

In law schools, we like to imagine that racial bias happens somewhere else. We acknowledge that it occurred in the past and that some of our students still suffer inherited deficits. We also know that it happens in communities outside our walls, where bad things of all types happen. We may also concede that bias occurs in earlier stages of education, if only because many minority students attend low-performing schools.

We assume, however, that racial bias stops at our doors. Law schools, after all, are bastions of reason. Just as we refine “minds full of mush” to sharp analytic instruments, we surely wipe out any traces of bias in ourselves and out students.

This is a dangerously false belief. Race is a pervasive, deeply ingrained category in our psyches. The category may be cultural, rather than biological, but both science and everyday experience demonstrate its grip on us.

Humans, moreover, are exquisitely expressive and acutely sensitive. Micro expressions and body language convey biases we don’t consciously acknowledge. Other people receive those signals even more readily than they hear our spoken words. Reading the psychology literature on implicit bias is both humbling and eye opening. When designing cures for the racial grade gap, we need to grapple with our own unconscious behaviors–as well as with the fact that those of us who are white rarely know what it feels like (deep down, every day) to be a person of color in America.

For Example

Here’s one example of how difficult it may be to overcome the racial gap in law school grades. One useful technique, as mentioned above, is to give students supportive feedback on their work. To help minority students overcome stereotype threat, however, the feedback has to take a particular form.

On p. 162 of his book, Steele describes an experiment in which researchers offered different forms of feedback to Stanford undergraduates who had written an essay. After receiving the feedback, conveyed through extensive written comments, students indicated how much they trusted the feedback and how motivated they were to revise their essays. Importantly, students participating in the study all believed that the reader was white; they also knew that the reader would know their race because of photographs attached to the essays. (The experimental set-up made these conditions seem natural.)

White students showed little variation in how they responded to three types of feedback: (1) “unbuffered” feedback in which they received mostly critical comments and corrections on their essays; (2) “positive” feedback in which these comments were prefaced by a paragraph of the “overall nice job” kind; and (3) “wise” feedback in which the professor noted that he had applied a particularly high standard to the essay but believed the student could meet that standard through revision. All three of these feedback forms provided similar motivation to white students.

For Black students, however, the type of feedback generated significantly different results. The unbuffered feedback produced mistrust and little motivation; the Black students believed that the reader had stereotyped them as poor performers. Feedback prefaced by a positive comment was better; Black students were more likely to trust the feedback and feel motivated to improve. The wise feedback, however, was best of all. When students felt that a professor recognized their individual talent, and was willing to help them develop that talent, they responded enthusiastically.

Some researchers refer to this as the “Stand and Deliver” phenomenon, named for the story of a high school teacher who inspired his underprivileged Mexican-American students to learn calculus. Professors who set high standards, while conveying sincere signals that minority students can meet those standards, can close enormous achievement gaps.

Sincerity

The key word in the previous paragraph is “sincere.” To overcome stereotype threat and other forces restraining our minority students, it’s not enough to offer general messages of encouragement to a class. That worked for Jaime Escalante, the teacher who taught his disadvantaged students calculus, because he was talking to students who all suffered from disadvantage. Delivering the same message to a law school class in which most students are white won’t have much impact on the minority students. The minority students will assume that the professor is speaking primarily to the white students; if anything, this will increase stereotype threat.

Nor will individualized messages work if they follow our usual “overall nice job” format. I cringed when I read those words in the study described by Steele. How often have I written those very words on a paper that needed lots of improvement?

Instead, we have to find ways to convey individually to minority students that we believe they can meet very high standards. That’s a tough challenge because many of us (especially white professors) suffer from implicit biases telling us otherwise. Even if we use the right words, will our tone of voice, micro expressions, and body language signal those unconscious doubts?

Moving Forward

Some readers may dismiss my worry about unconscious bias; they may be certain that they view students of all races equally. Others may be discouraged by my concern, feeling that it is impossible to overcome these biases. Indeed, Steele and others have documented a phenomenon in which whites avoid close interactions with minorities because they fear that they will display their unconscious bias.

A third group of readers may whisper to themselves, “she’s overlooking the elephant in the room. Because of affirmative action, minority students at most law schools are less capable than their white peers.” That potential reaction is so important that I’ll address it in a separate post.

For now, I want to offer this thought to all readers: This will be hard. If we want to close the racial grade gap and help all students excel, we need to examine both our individual and institutional practices very closely. Some of that may be painful. If we can succeed, however, we will achieve a paramount goal–making our promises of racial equality tangible. Our success will affect, not only the careers of individual students, but the quality of the legal profession and the trust that citizens place in the legal system.

I will continue blogging about this issue, offering information about other cognitive science studies in the field. For those of you who would like to look at the study involving written feedback (rather than just read the summary in Steele’s book), it is: Geoffrey L. Cohen, Claude M. Steele & Lee D. Ross, The Mentor’s Dilemma: Providing Critical Feedback Across the Racial Divide, 25 Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 1302 (1999).

If you want to explore the field on your own, use the database PsycINFO and search for “stereotype threat” as a phrase. Most universities have subscriptions to PsycINFO; if you are a faculty member, staff member, or student, you will be able to read full-text articles for no charge.

More on Paid Clinical Externships

I’ve posted before about my support for a proposed change in Interpretation 305-2 of the ABA’s accreditation standards for law schools. The proposal would allow law schools to offer externship credit for paid positions. Today I sent an admittedly tardy letter to the Council, expressing the reasons for that support. For those who are interested, I reproduce the text below:

Dear Council Members:

I apologize for this late submission in response to your request for comments on the proposed change to Interpretation 305-2. I strongly support the proposed change, which would allow law schools to choose whether to offer externships with paid employers.

I have been a law professor for thirty years, teaching doctrinal, legal writing, and clinical courses. I also have a research interest in legal education and have published several articles in that field. My current interest lies in learning how lawyers develop professional expertise and in designing educational programs that will promote that development.

From my personal experience, as well as reviews of the cognitive science literature, I have no doubt that externships are a key feature of this development. Externships alone are not sufficient: In-house clinics provide pedagogic advantages (such as the opportunity for close mentoring and regular reflection) that externships are less likely to offer. A program of in-house clinics complemented by externships, simulations, and other classroom experiences, however, can offer students an excellent foundation in professional expertise.

When designing an educationally effective externship, the employer’s status (for-profit, non-profit, government) and student’s financial arrangement (paid or unpaid) are not relevant. This is because the educational institution controls the externship requirements. If an employer offering a paid externship balks at the school’s educational requirements, the school can (and should) refuse to include that employer in its program.

The key to educationally sound externships is close control by the academic institution. I suspect that some law schools (like other academic institutions) do not devote as much attention to externships as they should. The greater the school’s collaboration with the employer, the better the externship experience will be. This problem, however, applies to both paid and unpaid externships. The educational potential of externships does not depend upon the amount of pay; it depends upon the school’s willingness to supervise the externship closely—-and to reject employers that do not create suitable learning experiences.

Employers who pay law students may decide that they don’t want to participate in externship programs; they may find compliance with the program’s requirements and paperwork too onerous. This is not a reason to reject paid externships; it is an assurance that they will work properly. If an employer is willing to pay a student and comply with the pedagogic requirements of a good externship program, we should rejoice: This is an employer eager to satisfy the profession’s obligation to mentor new members.

This brings me to the major reason I support the proposal: Permission of paid externships will allow innovative partnerships between law schools and the practicing bar. As members of a profession, lawyers have a duty to educate new colleagues. Our Rules of Professional Conduct, sadly, do not explicitly recognize this duty. The obligation, however, lies at the heart of what it means to be a profession. See, e.g., Howard Gardner & Lee S. Shulman, The Professions in America Today: Crucial But Fragile, DAEDALUS, Summer 2005, at 13.

Our profession lags behind others in developing models that allow practitioners to fulfill their educational duty while still earning a profit and paying their junior members. Law school clinics and externship supervisors possess a wealth of experience that could help practitioners achieve those goals. Working together to supervise paid externships would be an excellent way to transfer these models, improve them, and serve clients.

I deliberately close by stressing clients. Many of our debates about educational practices focus on the interests of law schools, law students, and employers. For members of a profession, however, client needs are supreme. We know that an extraordinary number of ordinary Americans lack affordable legal services. We also know that businesses are increasingly turning to non-JDs to fill their legal needs as compliance officers, human resources directors, and other staff. If we want to create a world in which individuals and businesses benefit from the insights of law graduates, then we have to design educational models in which new lawyers become professionals while they and their mentors make a living.

Thank you for your attention. Please let me know if I can provide any further information.

Deborah J. Merritt

John Deaver Drinko/Baker & Hostetler Chair in Law

Moritz College of Law, The Ohio State University

The White Bias in Legal Education

Alexia Brunet Marks and Scott Moss have just published an article that analyzes empirical data to determine which admissions characteristics best predict law student grades. Their study, based on four recent classes matriculating at their law school (the University of Colorado) or Case Western’s School of Law, is careful and thoughtful. Educators will find many useful insights.

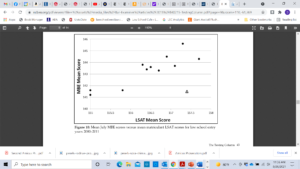

The most stunning finding, however, relates to minority students. Even after controlling for LSAT score, undergraduate GPA, college quality, college major, work experience, and other factors, minority students secured significantly lower grades than white students. The disparity appeared both in first-year GPA and in cumulative GPA. The impact, moreover, was similar for African American, Latino/a, Asian, and Native American students.

Marks and Moss caution that the number of Native American students in their database (15) was small, and that the number of Latino/a students (45) was also modest. These numbers may be too small to support definitive findings. Still, the findings for these groups were statistically significant–and consistent with those for the larger groups of African American and Asian American students.

What accounts for this disturbing difference? Why do students of color receive lower law school grades than white students with similar backgrounds?

“Something . . . About Legal Education Itself”

Marks and Moss are unable to probe this racial disparity in depth; their paper reports a wide range of empirical findings, with limited space to discuss each one. They observe, however, that their extensive controls for student characteristics suggests that the “racial disparity reflects something not merely about the students, but about legal education itself.” What is that something?

One possibility, as Marks and Moss note, is unconscious bias in grading. Most law school courses are graded anonymously, but others are not. Legal writing, seminars, clinics, and other skills courses often require identified grading. Even in large lecture courses, some professors give credit for class participation–a practice that destroys anonymity for that portion of the grade.

No one suspects that professors discriminate overtly against minority students. Implicit bias, however, is pervasive in our society. How do we as faculty know that we value the words of a minority student as highly as those offered by white students? Unless we keep very careful records, how do we know that we remember the minority student’s comments as often as the white student’s? These are questions that all educators should be willing to ask.

Another explanation lies in the psychological phenomenon of stereotype threat. When placed in situations in which a group stereotype suggests they will perform poorly, people often do just that. Scientists have demonstrated this phenomenon with people of all races and both genders. Math performance among White men, for example, declines if they take a test after hearing information about the superiority of Asian math students.

Legal education itself, finally, may embody practices that favor white students. Are there ways in which our culture silently nurtures white students better than students of color? I’d like to think not, but it’s hard to judge a matter like that from within the culture. Cultures are like gravity; they affect us constantly but invisibly.

Other Influences

I can think of three forces originating outside of law schools that might depress the performance of minority students. First, minorities may enter law school with fewer financial resources than their white peers. Marks and Moss were unable to control for economic background, and the minority students in their study may have come from financially poorer families than the white students. Students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds may spend more time working for pay, live in less convenient housing, and lack money for goods and services that ease academic study.

Second, minority students may have less social capital than white students. Students who have family members in the legal profession, or who know other law graduates, can commiserate with them about the challenges of law school. These students can also discuss study approaches and legal principles with their outside network. Even knowing other people who have succeeded in law school may give a student confidence to succeed. Minority students, on average, may have fewer of these supports.

In fact, minority students may suffer more than white students from negative social capital. If a student is the first in the family (or neighborhood) to attend law school, the student’s social network may tacitly suggest that she is unlikely to succeed. Minority students may also be more likely than white students to face family demands on their time; families may rely economically and emotionally on a student who has achieved such unusual success.

Finally, minority students bear emotional burdens of racism that white students simply don’t encounter. Some of those burdens are personal: the white people who cross the street to avoid a minority male, the shopkeeper who seems to hover especially close. Others are societal. We were all upset by the church massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, but the tragedy was much more personal–and threatening–for African Americans. How hard it must be to continue studying the rule against perpetuities in the face of such lawlessness and racial hatred.

What Should Law Schools Do?

I don’t know the causes of the racial disparity in law student grades. One or more of the above factors may account for the problem; other influences may be at work. Whatever the causes, the data cry out for a response. Even if the discrepancy stems from the outside forces I’ve identified, law schools can’t ignore the impact of those forces. If we’re serious about racial diversity in the legal profession, we need to identify the source of the racial grade gap and remedy it.

Law schools face many challenges today, but this one is as important as any I’ve heard about. It’s time to talk about the burdens on minority students, the ways in which our culture may aggravate those burdens, and the steps we can take to open the legal profession more fully to all.

No More Summer Associates?

Quinn Emanuel, one of the nation’s “superrich” law firms, is cutting most of its summer program. Rather than employ 50 summer associates, as it has in recent years, the firm will hire just 5-10. According to a memo from name partner John Quinn, the move will reduce expenses (with savings redirected toward signing bonuses for associates joining the firm on a full-time basis) and avoid the “unrealistic” nature of summer programs.

Quinn told Bloomberg BNA that he didn’t expect other law firms to follow suit; some members of the profession view Quinn Emanuel as “quirky.” On the other hand, he stressed the strong rationales for dumping summer associate programs: firms spend a lot on them, it is difficult to integrate students into the firm’s workload, students thus get an unrealistic view of firm life, and clients no longer want to pay for summer associate work (even at discounted rates). If firms took a hard look at summer programs, Quinn suggested, they would conclude that these programs don’t “make[] any sense.”

What will happen if other BigLaw firms follow the Quinn Emanuel lead? Here are some preliminary thoughts. I limit my discussion in this post to BigLaw firms. If the idea spread to smaller firms, that would have additional repercussions.

Elitism

Summer programs are one way–usually the only way–that students from lower ranked schools can demonstrate their worth. If firms eliminate summer try-outs, then how will they make permanent hiring decisions? I predict that they’ll recruit even more heavily from the most elite schools. A partner from a T50-but-not-T14 school may be able to persuade the hiring committee to take a summer associate from her alma mater. That’s a harder sell for a full-time associate position.

Quinn Emanuel’s retention of a very small summer program signals this shift to more concentrated elitism. The firm plans to continue hiring 5-10 summer associates each year who will be able to share their personal experiences with classmates. I think I can guess which 5-10 campuses will get those positions.

Money

Many law students rely upon summer money to pay living expenses and reduce reliance upon loans. For those who work at BigLaw firms, the money is substantial. According to the NALP Directory, the going rate for 2L summer associates at NY BigLaw firms is about $3,067/week this summer. That comes to $24,608 for an 8-week summer. Students owe taxes on that amount, but summer salaries still make a substantial contribution to student finances.

If other BigLaw firms follow Quinn Emanuel’s lead, the effective cost of attending law school will rise. Successful students may earn that money back during their careers, but the upfront investment will grow.

Hands-On Education

Summer associate programs play a useful role in exposing students to real-world law practice. Students return from these summers talking about their enhanced understanding of litigation (“I’ve seen a set of interrogatories!”), corporate work, and other practice areas. Some even meet a client or attend a legal proceeding.

At most law schools, BigLaw firms employ only a small percentage of students during the summer. Other firms, government agencies, corporations, and nonprofits offer as good–or better–practical experience to students. Still, it is worth asking what will happen if paid summer jobs start to decline. Where will students get the experiences that complement their classroom learning? Are law schools prepared to fill the gap?

Entry-Level Hiring

With its spare summer program, Quinn Emanuel plans to focus entry-level hiring on third-years and judicial law clerks. It’s easy to imagine the lean summer program, however, as the first step toward an emphasis on lateral and/or contract hiring. Will the Quinn Emanuel partners be willing to hire completely untested associates–or those trained only by judicial clerkships? Or will the current break with tradition lead to other changes?

Even if not at Quinn, what about other firms? One can imagine firms pruning both summer programs and first-year associate ranks. Most BigLaw firms are already fat around with middle, with a large number of income partners. Rather than hire more new associates, perhaps we will see a shift toward hiring laterals and contract lawyers.

Change

The most important implication of Quinn’s move is the fact of change itself. Six years after the Great Recession, firms are experimenting more–not less. They are continuing to ask “does this tradition make sense?” And they seem increasingly willing to change those traditions.

Law firms are notoriously slow to change but, when they do pursue a new course, law schools have to play catch-up. Quinn Emanuel hasn’t announced a proposal that a committee will study over the next academic year, ultimately proposing formation of a new committee to study the idea further. Quinn might have mooted this idea internally for some time, but change will follow quickly on the heels of the public announcement.

Quinn’s change will affect a small number of students at a small number of law schools. But what other changes are brewing, in BigLaw and elsewhere?

Honoring Obergefell

I’m elated by the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell. The decision affirms so many things I value: marriage, human bonds, tolerance, and constitutional principle. The decision also demonstrates the role that law plays in pushing us to examine prejudices; it gives me hope for further progress.

I value even the negative reactions to the opinion: they remind us that courts and legislatures maintain a delicate balance in a democracy like ours. I believe that the Obergefell majority properly interpreted and applied the Constitution but, to borrow a word from a different inspiring source, raucous discussion of our constitutional process is an essential part of that process.

Obergefell, of course, will jump into the law school curriculum. Professors and students will debate the majority’s reasoning, as well as the dissents’ attacks. They will explore Obergefell‘s implications for tax, family law, and other subjects. Even my Evidence book will include Obergefell in its summer supplement; it’s time to update the discussion of marital privileges.

All of this is as it should be. I challenge law schools, however, to take another, more difficult step in honor of Obergefell: to use this occasion to recognize how poorly we serve clients in the family law field.

Legal Needs

Marriage, as Obergefell recognizes, is one of our most important legal institutions. Marital status affects rights and duties related to “taxation; inheritance and property rights; rules of intestate succession; spousal privilege in the law of evidence; hospital access; medical decisionmaking authority; adoption rights; the rights and benefits of survivors; birth and death certificates; professional ethics rules; campaign finance restrictions; workers’ compensation benefits; health insurance; and child custody, support, and visitation.”

Couples need legal assistance to maintain this key status, to implement it, and (if necessary) to dissolve it. Yet hundreds of thousands of individuals cannot obtain that legal assistance. For many, the assistance is too expensive. For others, it is cumbersome or intimidating to obtain. Studies of the family law system reveal shocking gaps in legal assistance: In Milwaukee, 70% of family law litigants lack counsel. In California, 80% of family law cases include at least one pro se litigant. In Philadelphia, 89% of child custody litigants proceed without counsel. No city or state has produced a report showing that its residents are able to satisfy their legal needs in family-related cases.

Whose Problem Is It?

We’ve talked for decades about addressing these legal needs through increased legal aid funding or enhanced pro bono efforts. But governments are already struggling to balance budgets, and taxpayers show little inclination to raise taxes. Lawyers praise pro bono, but our efforts chronically fall far short of our rhetoric. Many of us lack the skills and experience needed for effective family law representation.

To solve the legal crisis affecting families, we need to start in law school. We need to champion the importance of representing individuals with family-related legal needs. Divorce, child custody, and other domestic relations work have languished at the bottom of the status heap in law practice. If we believe in Obergefell, it’s time to change that.

We have to teach students the skills they need for success in family law practices. This is a tough practice area, with particularly challenging issues of client counseling, negotiation, and ethical responsibilities. Doctrine matters in this area, but so do skills. Family law practitioners are already struggling to serve their clients and make ends meet; we can’t rely on them to educate law graduates on the skills they missed in law school.

Equally important, we need to devise systems that deliver these essential legal services more efficiently and economically. Researchers, educators, and practitioners should work together to design new systems and test their impact. Unbundled services? Limited license professionals? Online resources? Prepaid plans? What combination of these approaches–and others–will best meet the needs of potential clients?

Professional Responsibility

Lawyers own the legal profession. We control entry, education, and practice. Society allows us to bar others from performing our work. That ownership confers a responsibility: to operate the profession in a manner that assures access to needed services.

Legal educators sometimes stand apart from the profession, forgetting our key gatekeeper role–and the financial benefits we derive from that status. We are the ones who choose potential lawyers and chart their course of study. We also have the resources to research new methods of delivering legal services. We, along with other lawyers, bear responsibility for persistent flaws in the legal system. It’s time to act on that responsibility.

Access to Justice

It may seem odd to honor Obergefell by discussing a practice area that reflects the heartaches of marriage more often than its joys. I hope that none of the couples who marry in the coming months will ever separate, fight over their children, or suffer domestic abuse. But at least some of them, both same-sex and opposite-sex, will.

The legal system recognizes grand ideals of justice, but it also acknowledges our human weaknesses. We make mistakes. We commit crimes. We break contracts. We abandon our partners and fight over our children. Sometimes we even abuse the people we love most.

Laws exist to cope with all of our mistakes. In the family law system, a good attorney can help change personal tragedy to a new beginning. At the very least, an attorney can mitigate the damage. But today, a majority of Americans face these personal and legal tragedies without sufficient guidance. It’s up to us–the gatekeepers, educators, and researchers of the legal system–to design a better system.

The Challenge

I challenge every law school to create a clinic or post-graduate firm focused on family law issues. If you already have one, make it better. Encourage faculty to work with practitioners, designing and testing new systems of delivering legal services. If none of your current professors are interested in improving the delivery of legal services, hire one who is. Teach students that family law is an essential area of law practice, and help them create sustainable practices. Enforce the promise of justice for everyone who has ever been part of a family.

Fee Shifting

I recently interviewed Pete Barry, a lawyer who represents plaintiffs suing debt collection agencies for violations of the Fair Debt Collections Act (FDCA). You can listen to the interview in this “I Am the Law” podcast.

Pete is quick to acknowledge that his clients should pay their debts; he’s not in the business of shielding deadbeats. At the same time, Congress found that abusive debt collection causes job losses, marital breakups, and bankruptcies–all events that hinder debt repayment. To prevent these outcomes, Congress outlawed some debt collection practices.

Rather than create an agency to police debt collection, Congress chose to rely upon private enforcement. When a plaintiff establishes an FDCA violation, she recovers actual damages, court-ordered compensation of up to $1,000, court costs, and an attorney’s fee.

The fee shifting produces some eye-opening results. As Pete explains in the podcast, many defendants know that they’ve crossed the line and are willing to settle. Unless the plaintiff has provable actual damages, she may recoup only $1,000 through settlement. Pete’s court-approved hourly rate, however, is $450. He tracks his time carefully and defendants pay those bills when they settle. Even an easy case can generate $4,500 in attorney’s fees.

Did You Learn This in Law School?

Pete’s practice intrigues me because of its business model. Rather than rely upon clients to pay his bills, Pete built his practice around a federal fee-shifting statute. He notes that there are many such statutes, and that too many lawyers overlook them when designing a practice.

After talking to Pete, I realized that law schools also overlook these statutes. Some fee-shifting laws, particularly those related to civil rights, appear in the law school curriculum. Even courses teaching those statutes, however, tend to focus on substantive rules rather than the potential for attorney’s fees.

When we do talk about attorney’s fees in law school, we usually discuss the policies surrounding fee shifting. We may use noble language like “creating private attorneys general,” but we rarely analyze the potential for these statutes to create a viable law practice.

Vindicating Congressional Policies

Congress didn’t create fee-shifting statutes to support lawyers. Instead, these statutes protect important interests–primarily ones held by the poor and middle class. Potential plaintiffs have suffered from our lack of attention to these statutes.

Imagine if the required 1L year included a course on fee-shifting statutes. That course would deepen students’ knowledge of statutory law, highlight rights that Congress (or state legislatures) considered important enough to enforce through attorney’s fees, and expose students to injuries that disproportionately affect poor, middle class, and minority clients. The course would also remind students that legal remedies aren’t free and most lawyers earn their living from private clients.

I doubt that many law schools (if any) would add my proposed course to the first-year curriculum. Just imagining such a course, however, helps me see the distortions in the current curriculum. Our traditional courses help students master fundamental legal concepts, like negligence or breach of contract. I suspect, however, that we could teach the same concepts through modern statutes–and perhaps give students better grounding in the statutory remedies that define most contemporary legal rights.

At the same time, we would focus students on a fact that is fundamental to both the rule of law and their future as practicing attorneys: Lawyers can’t promote justice unless someone pays their bills. If law schools paid closer attention to this truth, including the business side of law practice, we might widen the scope of legal services.

The Appellate Classroom

Critics of legal education often note the primacy of appellate law in law school classrooms. Our doctrinal courses, after all, rest primarily on appellate opinions. But the focus on appellate advocacy is even more pervasive than this: Our “Socratic” questioning follows the cadence of an appellate argument.

The professor stands at the front of the room, often on an elevated platform. She poses a question, which a single student addresses. Some questions involve the facts of the underlying case; others address application of the legal principle to other alternative fact patterns. After the student answers, the professor poses another question.

If you doubt the similarity to an appellate argument, try this experiment: Attend an appellate argument in a local courthouse, then witness a traditional law school class later the same day. I once did this, entirely by accident, and I was astounded by the similarities.

Preparation for Lawyering

Our doctrinal courses thus give students repeated practice for appellate lawyering. Their raw materials are appellate cases, and classroom discussion resembles oral argument. The legal reasoning conducted in doctrinal classes consists of reconciling precedents and applying them to new fact patterns.

Some of my colleagues argue that the latter task prepares students for other types of practice. We may, for example, ask a student: “How would you counsel your client to respond to this decision?” Or, “what if you advised a client to do X? Would that fall within the court’s holding here?”

These questions, however, are like the ones that appellate judges ask as they probe the doctrinal reach of a possible holding. The substance is the same as questions asking “if I accept your argument, how would that affect individuals who do X?” Or, “how will clients change their practices if we adopt your interpretation of the statute?”

These questions about “advising clients” do not give students practice in client counseling. If a lawyer were representing a real client, the answer to the above classroom questions would be something like: “It depends how much the client has to spend, both on legal representation and on modifications to her business. It also depends on how much the client cares about Y rather than Z. I’d also need to ask the client about potential alternatives.”

Experiential Education

It’s essential to recognize these facts about doctrinal classes as law schools embrace more experiential types of learning. Many types of experiential learning aid doctrinal understanding; I use simulations and other exercises in my Evidence course for just that purpose.

Most of these exercises, however, do not redress the appellate tilt in our classrooms. We need much more fundamental shifts in doctrinal courses to accomplish that. Alternatively, we need to expand the time devoted to simulations and clinics that focus on lawyering outside the appellate practice.

Very few law school graduates find work as appellate lawyers. Most clients need other types of assistance. In order to serve both those students and their clients, legal educators need to reduce the dominance of appellate lawyering in our curriculum. How do lawyers use doctrine and interact with client outside of that setting? That question lies at the root of constructive pedagogic change.

About Law School Cafe

Cafe Manager & Co-Moderator

Deborah J. Merritt

Cafe Designer & Co-Moderator

Kyle McEntee

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Around the Cafe

Subscribe

Categories

Recent Comments

- on Experiential Education

- on Scholarship Advice

- on ExamSoft: New Evidence from NCBE

- on COVID-19 and the Bar Exam

- on Women Law Students: Still Not Equal

Recent Posts

- Experiential Education

- The Bot Takes a Bow

- Fundamental Legal Concepts and Principles

- Lay Down the Law

- The Bot Updates the Bar Exam

Monthly Archives

Participate

Have something you think our audience would like to hear about? Interested in writing one or more guest posts? Send an email to the cafe manager at merritt52@gmail.com. We are interested in publishing posts from practitioners, students, faculty, and industry professionals.