June 28th, 2017 / By Gilbert A. Holmes

June 28th, 2017 / By Gilbert A. Holmes

Gilbert A. Holmes is Dean and Professor of Law at the University of La Verne College of Law

In July of 2016, graduates from ABA-approved law schools in California had a first-time General Bar Examination pass rate of 62 percent, and all bar takers in the state had a first-time pass rate of 56 percent. These numbers are down from previous years, sparking debate, discussion and deliberation about the reason for the decline and what can be done about it.

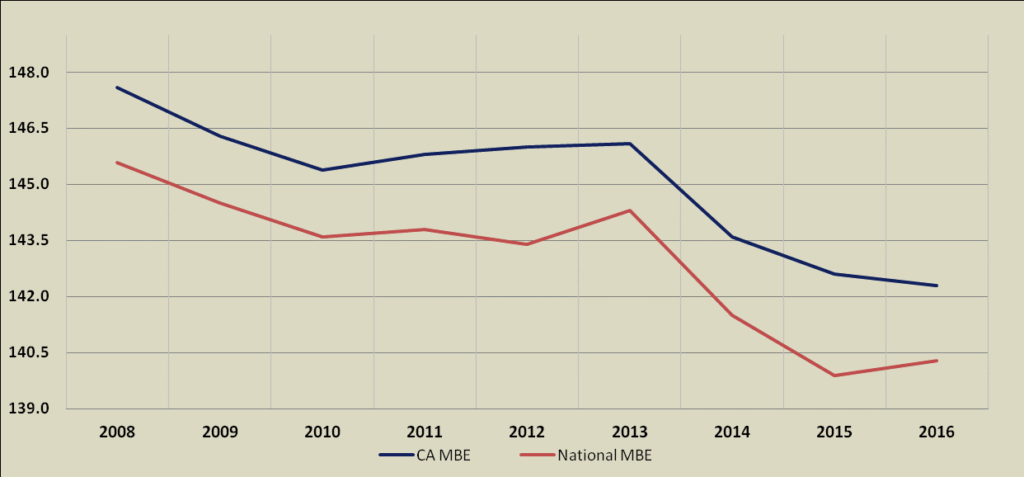

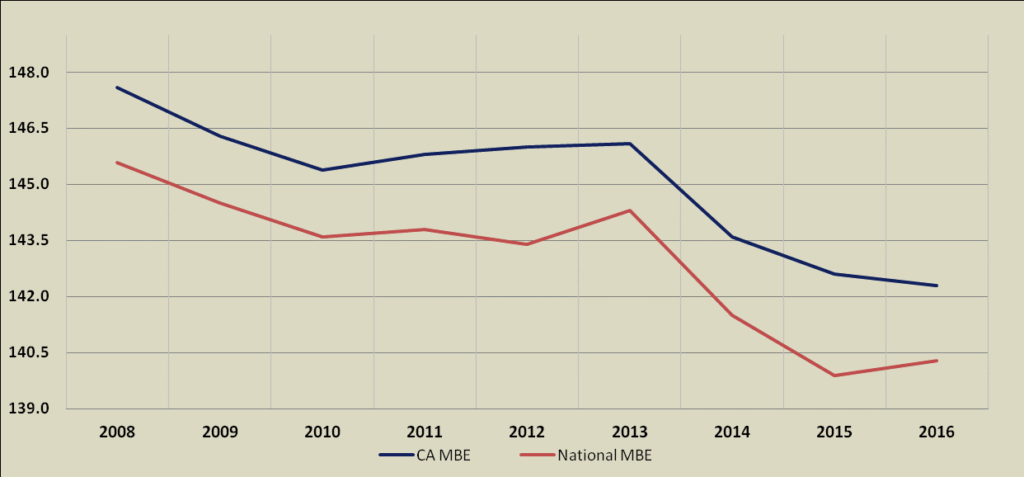

Deans of ABA-approved law schools in California have been calling for a lowering of the cut score that serves as the basis for grading of the exam. California has the second highest cut score in the country. It also has the lowest pass rate, even though researcher Roger Bolus reported to the State Bar of California that the state’s bar exam takers perform higher than the national average on the only portion of the exam that every state except Louisiana administers—the MBE.

The State Bar has responded to this call by engaging in a number of studies about the content and validity of the bar exam and the California grading system.

Amid this discussion, two law professors, Robert Anderson IV and Derek T. Muller, from Pepperdine University School of Law, distributed an unpublished article entitled “The High Cost of Lowering the Bar.” In it, they assert that lowering the cut score on the California bar exam will likely increase the percentage of lawyers who are disciplined by the State Bar over the next 35 years.

The article relies on questionable statistical analysis and assumptions, and has been very thoroughly debunked by Professor Deborah J. Merritt of the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University. I agree wholeheartedly with Professor Merritt’s analysis. But there is an even more important aspect to this question that she, too, misses. And that is the extremely high cost of not lowering the cut score, which is now being paid by both the public and law school graduates.

High Cost Number 1: The current system is depriving society of qualified attorneys.

Anderson and Muller posit that there would be a 1 percent increase in the number of disciplined attorneys over a 35 year period for every 10 point reduction in the cut score.

The current cut score in California is 1440. The current cut score in New York is 1330. According to a study commissioned by the State Bar and conducted by Roger Bolus, reducing California’s cut score to New York’s for the July 2016 bar exam would result in an estimated 750 additional graduates from the California ABA law schools and numerous other individuals passing the bar and presumably being admitted to practice in California. (The first-time pass rate from California ABA law schools would increase from 62% to 86%.) Applying the Anderson/Muller projection to this group, 75 of the California ABA graduates and 10 percent of the other individuals would be disciplined by the State bar between 2016 and 2051, with none being disciplined until 2026.

As alarming as that may sound, the projection ignores the approximately 675 attorneys who would not be disciplined and who would be available to represent individuals, corporations, small businesses and community organizations, and serve as leaders in legislative bodies, communities and public and private institutions. Our state, communities and citizens deserve access to this cadre of licensed attorneys.

Opponents suggest that the job market cannot support another 750 or so lawyers per year, not including the additional individuals who would pass the February exam. Besides the fact that market concerns are not the purview of the State Bar and while there might be some truth to the perception of the elasticity of the “job market,” it is important to remember that licensed attorneys have many valuable roles to play in society beyond the traditional legal field.

Some bring their skills and training to careers in business, not-for-profit organizations, government, education and community organizing. They understand rule generation, interpretation and implementation, and assist us in maintaining a society based on the rule of law. The job market will always have room for these professionals.

High Cost No 2: The needless financial and emotional toll on law school graduates and their families.

The California State Bar acknowledges that the ultimate pass rate for graduates of ABA-approved law schools is high. The two-year bar pass rate for California ABA-approved schools was 95% in 2008 and 89% in 2014, the last year for which there is a two-year pass rate. This means the vast majority of law school graduates pass the bar eventually.

There is not a proponent or opponent of the current bar exam grading process in California—or in any jurisdiction—who believes that people who take two or three attempts to pass the bar actually learn additional law or procedure between sittings for each exam. We all know these individuals become better masters of the test as opposed to becoming better masters of the law.

But while these individuals are improving their mastery of the test, they incur additional debt, have to rely on the financial support of others, delay their careers and possibly miss out on job opportunities. They also suffer the disappointment and anxiety that surrounds failing and retaking the exam.

They pay these transaction cost to what end? To eventually get what they should have or could have received with a lower cut score.

When you look at the Anderson/Muller analysis through these lenses, it is clear that not lowering the cut score assesses many law graduates with an unnecessary and devastating tax, and unfairly deprives society of too many good attorneys.

Undoubtedly, some individuals will not pass the bar exam even with a lower cut score. And, perhaps some people will never pass the bar exam. There is nothing wrong with that. But the price we – society and the individual bar takers – pay for a system that does not ultimately benefit us is too high to justify solely to maintain the system we have in place t

Data, Rules, Bar Exam, California State Bar

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.

Law School Cafe is a resource for anyone interested in changes in legal education and the legal profession.